Spotlight on Tristan Spinski

Nov 16, 2013

TID: These are beautiful - Please tell us about the how the image came about.

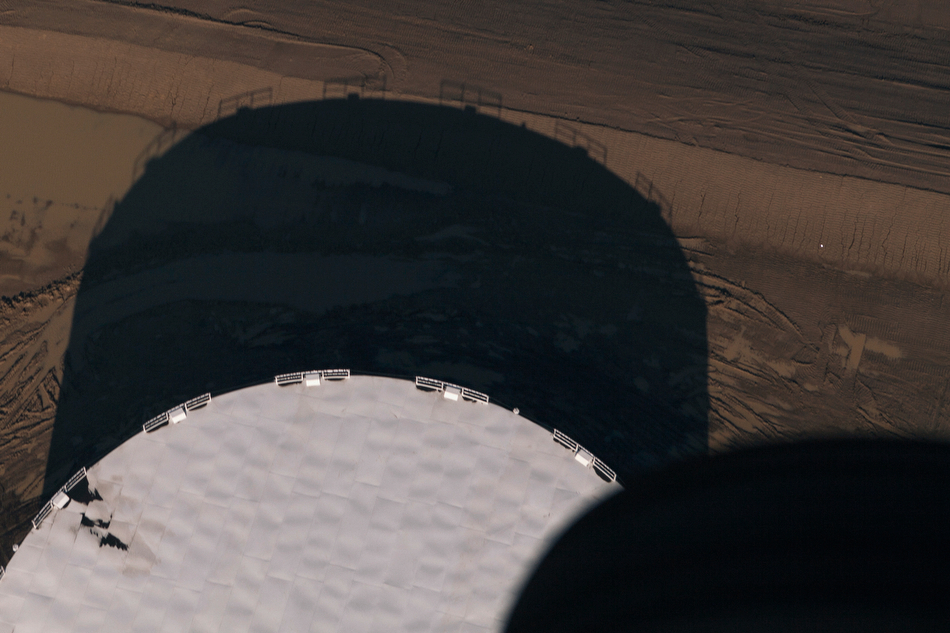

Tristan: I made these images in June during an assignment in North Dakota for Bloomberg Businessweek, then some of my favorites have now run the newly launched POLITICO Magazine this past week. The goal was to provide aerials of fracking operations and trains transporting oil out of the Bakken Formation — an underground rock formation with enormous reserves of oil and natural gas that stretches from North Dakota and Montana into Canada. My standing order was to photograph the trains in an “artful way.”

TID: Were there issues or challenges you encountered during the coverage of this event, and how did you handle them?

Tristan: This shoot had a lot of typical challenges — it was a new client, I got the call last minute (and was recommended by a friend who was called first but already booked), the location was 700 miles from where I got the call. All that stuff — you just have to make it work. Whatever it is, you make it work. It could have made sense to catch a flight to Bismarck, North Dakota the day before, but I opted to drive since I’d never been that far north and I really enjoy driving long distances to assignments. It gives me the chance to hash out ideas, as well as be inspired by new scenery. I also like the idea of possibility. If you fly, you pretty much know what‘s going to happen. But driving that kind of distance really opens things up to the unknown.

I reserved a small plane for two days later and made plans to meet just before sunrise. I wanted to make sure I was making the most of the early morning light. From my time working at a newspaper I’ve had the opportunity to iron out the kinks on shooting aerials and understand some basic principals. I usually start by shooting wide to capture the vastness of what’s below. I shoot A LOT, as there will be many unusable frames in that dynamic of a working environment. There are things you can do: Try to keep your horizons level. Pre-focus so you aren’t hanging out the window with the wind in your face, making you tear up. More importantly though, I like to recite as many “Top Gun” lines as possible during aerial shoots, usually starting with “Talk to me, Goose.” Incidentally, I also sang “Take My Breath Away” at karaoke last week.

I’m dependent on the pilot to take me to the best places to see the oil trains. I wanted to see the fracking sites, but the trains were my first priority. The pilot knows the area and takes photographers up fairly regularly, so I’m in good hands. He was also open to flying fairly low and slow, and was extremely accommodating. Most of the time he was steering the plane at a steep embankment, and leaning over to prop the window open as I hung out to shoot. Usually the window stays open with the wind, but we were flying so slow that it kept crashing down on me.

All of the logistics aside, this assignment came about at the perfect time for me. I’ve had a real shift in priorities with my work. My father died last winter and I’ve been doing a lot of soul-searching about what I do, what it means, and who I really want to be as a photographer. I'm moving towards projects that revolve around land use, natural resources and people's interaction with the landscape.

I know this isn’t a novel idea, but it's taken me time to find an area that I'm truly interested in - as opposed to subject matter that I feel obligated to be interested in. And the ridiculous part is that I've had a really tough time figuring out that I need to make photographs that I would want to look at.

TID: Wait, explain that - what do you mean? What are "photographs you want to look at?"

Tristan: I spent a few years working on staff at a newspaper. That experience was very good in so many ways. When you have 2-3 assignments a day for years, you deal with a huge spectrum of people and situations: in the morning you can be photographing an Easter Egg hunt, only to be called out to a wild fire later the same day. You're switching gears constantly and are able to hone a degree of efficiency with approaching people, finding moments and workflow.

Best case scenario, you’re also working with a staff of photographers and editors trying to achieve the same thing, so it can become a group effort. But one of the challenges can be a flip side: Within the team - when you work for the same publication and the same editors - you can lose a bit of yourself and your personality in the work. And that's totally appropriate for a number of reasons. It's not about you. It's about the story. It's about communicating what's happening and providing context in the most efficient way possible. It's about the community, and your responsibility to your community as a photojournalist.

I think that my time working on staff was very constructive for all of those reasons, but I also think that I began to become a photographer who photographed for other people, mainly my editors, rather than myself. There was a "look" to the newspaper, and just through osmosis you eventually photograph within the parameters of that look. It's bound to happen anywhere, so it's not a criticism of any particular publication. It's just a byproduct of working in the same place for a while.

So I found myself making photographs that were well-received. I mean, my editors weren't doing cartwheels or anything, but I could go to an assignment and return with something that would be appropriate and everyone was happy — nice light, a good moment, a balanced, well-composed frame — all that good stuff. But there was something missing for me.

TID: How did you overcome or work through this?

Tristan: There are some photographers who don't look at other photographers' work. Maybe they feel it will influence them or corrupt their own eye. I'm not one of those photographers - I constantly look at other's work and to get inspired. So I was looking at other photographers' work, and realizing how far I was from that caliber of photography. I was looking at Trent Parke, first his black and white work, and then later his color work — which I still revisit often and sit in awe as to what someone can do with a camera. I was looking at Christopher Anderson, Danny Wilcox Frazier, Carolyn Drake, to name a few. I was also looking at some of the classic portraitists like Diane Arbus and Richard Avedon, as well as contemporary portrait photographers like Chris Buck and Dan Winters. There are so many photographers that inspire me.

I finally decided that I needed to leave the staff job and come to my own conclusions, my own vision, just like so many of my heroes had - on their own terms. I really didn't know how or what that would look like, or will look like. But I know that I'm in love with photography that exists in the space between art and documentary - photography that embraces and communicates a feeling, an idea, a concept, but within the parameters of nonfiction. This may sound vague or ridiculous, but that's how I feel most of the time: vague and ridiculous. And so the images you see from me now are the results of me taking these first steps to find myself in photography.

TID: I know that beyond these photographic inspirations, your father and his viewpoint has been a major catalyst to how you work.

Tristan: I think I’m in the process of letting go of my ego, expectations and preconceptions, and really being disciplined about that letting go and allowing myself to start becoming the photographer I want to be. This has everything to do with my father, who had a brilliant career as a ceramic artist — making statements about mass consumerism, working class know-how and intersections between religion, capitalism and culture. My last visit with my father, before his stroke, he said that to be a "chronicler of the times" was the most important thing he was able to do with his art and his career. I never thought of his sculptures in that light. And I'd never really thought about my photography that way. Of course, I've had plenty of assignments that, in a very narrow scope, show what's happening in the world around us. But I'm talking about the big picture: what is happening in North Dakota, in the Bakken Formation, has enormous economic, socio-cultural and environmental ramifications. And it's not just a shift in priorities for me, it's also my aesthetic and approach. So much of my work up to this point has been clever, at best. I don’t want to be a clever photographer.

So as I leaned out the window of the airplane over the Bakken Formation, I didn’t need to shoot extra wide or engage in any “clever” activity. What played out in front of my lens was a circumstantial dance of good light, amazing shapes, lines and geometry. And all that in the context and conversation about energy, consumption, land use and environmental implications. These photographs are part of my first steps in that direction. “Simplify,” as my father said. Not in a lazy sense, but more in the way of letting the subjects and the subject matter speak for itself a bit more. But it's a fine line. I want to communicate the feelings I feel when I see this, but without being overbearing. But I see things in a fairly romantic way. So it becomes a bit like cooking with good ingredients. Where and when do you show restraint? I don't know yet. That's what I am working towards.

I’m continually finding myself through my work. And I’m really enjoying my father's voice in my head as I go through this creative journey.

TID: You said earlier: “I’m in the process of letting go of my ego, expectations and preconceptions, and really being disciplined about that letting go.” How are you making this process?

Tristan: When I first became a photographer I was convinced that I would cover conflict. I came to photography through writing actually. I was reading writers like Michael Herr, who did a brilliant book, Dispatches, which was a series of vignettes from the Vietnam war. Backing up even farther — my father served in the Marine Corps in Vietnam, and was injured, almost ruined, by the war. I grew up listening to his stories. They weren't meant to glamorize or glorify his experiences in the war, but my dad was my hero and if he was damaged, I wanted to be damaged. In a way I thought that through journalism, and then through photojournalism, I could be like my dad: brave, thoughtful and experienced in the ways of the world.

He had earned the right to be whoever he wanted to be. I saw that in a very matter-of-fact way. My father was an artist. But he wasn't coming from a place of highfalutin luxury or self-indulgence. He was a Marine who was coming from a place of betrayal. He had bought into the concept of "God and Country" before Vietnam, but watched his friends die, and did unforgivable things for a cause that he didn't feel was worthy. He came back to an America obsessed with consumerism and celebrity. It was a corruption of principals for him. It was a betrayal on the highest and deepest levels.

So my father turned to art to make his statement. And there's nobody more worthy, more deserving (in my opinion) than my father of having the right to comment on these larger issues. So that's what I wanted. I wanted to right to be able to comment on the world around me, even if it meant damaging myself and risking everything. I found photojournalism to be my conduit to that place. I couldn't articulate any of this at the time, but I've just been doing a lot of thinking about what I do and why I do it. Being honest with yourself is a lifelong pursuit. It sounds so simple. But to recognize your motivations and realize "the why" is something I'm fascinated with.

After getting married and working in newspapers for a few years I began to see a shift in the work I was inspired by. I wasn't looking so much to the conflict photography, as much as I was looking to portraiture and of a genre that straddles the space between art and documentary. But there was always that drive to prove myself — both to my peers, my family, and to myself. I didn't so much want to cover conflict. I just wanted to get past it and be a photographer who has covered conflict. I was obsessed with achieving a past tense, a resumé, in a way. And that's an absurd, ego-driven goal. It's not fair to the people who love you. And it shouldn’t be about you. It should be about the people and issues you’re photographing.

There are photographers who are well-versed in this way of working. They genuinely care about the work they do, the people they cover and the cobweb of geopolitical issues surrounding conflict. I have no experience in that world. And up to this point, both with my writing and my photography, I've made every effort to work and document my own back yard. I've always wanted to explore and understand the issues that impact the United States. I love understanding the nuances of gesture, expression and language that only comes after a lifetime in a place.

In my instance, it's here in North America. And it's in that space that I love working and photographing the most. I am especially fascinated with the spectrum of issues involving land use, natural resources, environmental degradation and people's relationship to the landscape. Maybe that's not as romantic or important as going abroad for war, but that's me. That’s what I truly, deeply care about. And now that I'm discovering a purpose with my work and engaging in a larger conversation about the landscape and the choices we make, I'm honored to be a part of that conversation and so excited to see where it takes me.

BIO:

Tristan Spinski (b. 1978) grew up between the foothills of southern Ohio and the Mid Atlantic. During high school Tristan played football, and, according to his coach, couldn’t catch worth a damn.

Tristan earned a Master's Degree in journalism from UC Berkeley. He worked as a landscaper, a busboy and an oyster shucker before joining the photography staff at the Naples Daily News in southwest Florida.

A founding member of GRAIN, a photography collective, Tristan’s editorial clients include Rolling Stone Magazine, Mother Jones Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, The Wall Street Journal, CNN.com, AARP Bulletin, and FRONTLINE/World, and he has served as an adjunct professor at the University of Delaware.

Tristan currently lives in Wilmington, Delaware with his wife, Sarah, and dog, Billie Ocean.

LINKS:

www.grainimages.com

www.tristanspinski.com

photo by Greg Kahn