Spotlight on Nathan Morgan

Nov 1, 2012

TID:

Thanks, Nathan for being a part of this. We're glad to talk with you about the above image.

NATHAN:

Well first of all, thanks for this amazing opportunity. I'm a huge fan of The Image, Deconstructed and to be featured is quite an honor. So thanks.

I made this image in 2008, just months into my first full-time job at the Midland Daily News.

Here's the caption:

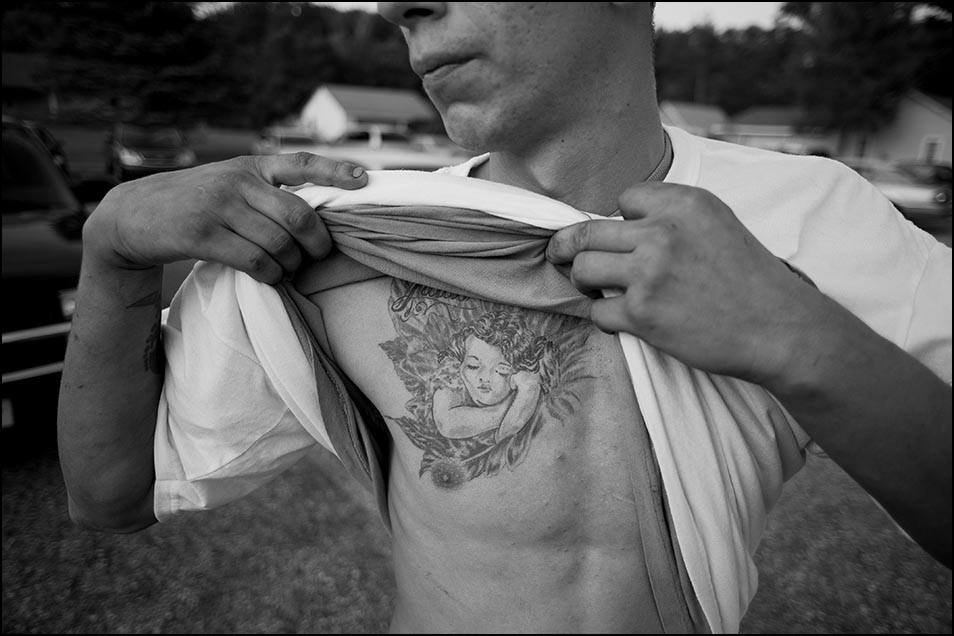

Sammy Quinones, father of 4-year-old, Jada Jean Quinones, who was killed in a June 13, 2008 car accident at the intersection of M20 and Vance Road, in Midland, Mich. shows a tattoo that he got in memory of Jada shortly after the accident. Quinones and his family are strong proponents for the installation of a traffic signal at the intersection where his daughter was killed. Quinones, who drives through the intersection daily on his way to work, said, "Until I see a light there, I won't be happy."

TID:

What was the original assignment? How did you find out about the tattoo?

NATHAN:

I was working the evening shift, and when I came in that afternoon I met with the photo editor, Ryan Wood, to discuss my assignments. My first assignment of the day was to spend time with a former high school teacher who had suffered a brain injury in a recent car accident. Her father would be visiting her at the rehab facility where she was living, and we had been given access.

The second thing I had to shoot was the assignment that lead to this image. It was just basic coverage of a community meeting that was being held at a local church to discuss several serious traffic problems and the possible installation of a traffic signal at a dangerous intersection just outside of the Midland City limits. When Ryan told me about the meeting, neither of us were very hopeful, and actually, I think he even apologized for the assignment. Meetings were generally something we tried to avoid photographically, but given its newsworthiness and the community's interest in the subject, we couldn't really afford to miss this one.

TID:

Was there any reaction or outreach from the community?

NATHAN:

Midland is a pretty conservative community. We often got phone calls and emails and even letters to the editor for running stuff like this. But, I don't remember any negative reaction to this image. I'd like to say that it changed the mind of officials at the Michigan Department of Transportation and that a traffic signal was installed the next day, but that wasn't the case either. I do think that our coverage of this event was pretty unique though, and that some needed attention was brought to the subject. Had we not shot this event I don't think it would have been made much impact. And really it's a good lesson in arriving to an assignment early. If I had went just as the meeting was starting I would have totally missed this opportunity.

I remember that shortly after the accident, the community placed a lot of blame on the mother, Katie. They blamed her for Jada's death. Jada was not in a car seat, which at the time Michigan Law didn't require car seats for children age 4 and up. I think the paper even had to remove comments on the original accident story because they became so vicious. I can't say for a fact, but my hope is that this image helped people connect more with the Quinones family and what they were going through.

TID:

How do you approach people in sensitive situations/topic or who have suffered loss and make storytelling images?

NATHAN:

I'm not a super pushy guy. I also don't take no for an answer very easily. But when it comes to a situation like this, when you're dealing with parents who just recently lost their 4-year-old daughter, you really can only go as deep as they'll let you. Had they blown me off when I first approached them, I would have never made this image. On most assignments I try to find commonalities with my subjects, but with a situation like this, it's very difficult. I've never felt the pain of losing a child, and I hope I never do. Now that I'm a father myself, I totally relate to this image in a different way than when I shot it.

In most cases if you can truly empathize with the subject it helps. The Quinones family wanted to have their story heard, and I was able to give them that.

When I arrived at the church where they were having the meeting, it was getting late, but the light outside was still nice. I didn't want to go inside until I absolutely had to, so I began chatting it up with some of the people who where gathered outside. Immediately I gravitated toward a lady who was wearing a shirt in memory of Jada Jean Quinones. We had covered the accident and had done a little bit of follow up, but I was familiar with the story mostly because I lived (literally) right next to the intersection where Jada was killed. I drove through it every single day on my way to work and could even see the makeshift memorial for Jada from my front widow. Even though I wasn't in Midland when the accident occurred, I felt somewhat connected to the incident, to Jada and to her family.

I heard that some of them would be coming to the meeting, but I wasn't sure if her parents would be there. I introduced myself to the lady and quickly discovered that she was Jada's mother, Katie Quinones. She was outside waiting for her husband, Jada's father, Sammy Quinones, who was coming to the meeting directly from work. Their plan was to show up to the meeting in full force. They wanted to have a presence and show why this traffic signal was necessary. Their argument was that the signal would have prevented their daughter's death. Which is probably true.

Katie and I talked for a bit and when Sammy arrived, Katie gave him a memorial shirt and button. The shirts were white with a smiling portrait of Jada in the center surrounded by the words "In loving memory of Jada Jean Quinones." After Sammy was dressed I complimented his shirt, and that's when he mentioned the tattoo.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image? How did you handle and overcome these problems?

NATHAN:

None really. Sammy was so forthcoming with the fact that he had the tattoo, that it made my job easy. Usually when you're in a situation that's sensitive like this, you never really know how people are going to react to your presence. When he mentioned that he had just gotten a tattoo in memory of his daughter, without thinking I immediately asked to see it. If he was open enough to tell me about the tattoo, I figured that he would be willing to share it with me.

I half expected it to look exactly like the design on their t-shirts, so I was surprised when he lifted his shirt. The image of Jada was more angelic in nature and she was sleeping. He said that it was based on a photo of her. He thought it was nice because she looked so peaceful.

The only problems were technical really. While I was talking with the family, the sun was dropping fast. By the time Sammy showed me his tattoo, it was practically dark outside. I had not re-exposed, so the image was actually a couple stops under. Luckily it was RAW.

TID:

Was this posed? If so, how did you approach him and make it feel organic?

NATHAN:

Sorta. I would definitely consider it a portrait, but I didn't really pose it. He was reacting to my request to see the tattoo, but I didn't take the time to pose the image. I asked, he obliged, I fired off a few frames, and then it was over. I think that's what gives it a more documentary feel. Had I taken the time to pose this photo, it most likely would have sucked. I'm not good at getting people to "act natural." That's why when I shoot documentary portraits, I try not to influence the situation too much. I think when you start posing your subject, too much of the photographer shows up in the image. This was totally off-the-cuff, but I think it works. Sammy is being himself, sharing the tattoo with me just as he would with anyone else.

TID:

It was an interesting choice to leave him anonymous and let the tattoo become the identity of the photograph. What was your thought process while you made the image?

NATHAN:

Good question. When I was making this image I felt that it was more about the tattoo and Jada. Shooting the tattoo tighter would read better, but at the same time I wanted to also include some details of Sammy. His fingernails, the scars on his arms and chest. His slim physique. Even without seeing his face, you know that Sammy isn't someone who has had an easy life, which is compounded by the fact that he also just lost his daughter.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

NATHAN:

Los Angeles Times photojournalist Rick Loomis said something once to me when he was my coach at The Mountain Workshops. "You're a human first, and a photographer second." I'm not sure if he originated this saying, but it's stuck with me. When making an image like this, I don't want to be thinking about myself or even the image for that matter, I want to be thinking about this family and their loss, which despite my best efforts is sometimes hard to do. It's just so easy to get caught up in the whole process that we forget to stop and actually experience what is happening right in front of us. It is a goal of mine – and I'm not saying that I always live up to it – but it's a goal of mine to connect to my subjects. Not just for show or to build a temporary rapport, but to actually connect, to put myself in their shoes. I believe that if you do this, everything else will work out.

TID:

Finally, can you talk more about any thoughts or advice you have on community journalism?

NATHAN:

Community journalism is what I do. With the exception of my internship at the Commercial Appeal, I've only worked at small papers. I see the work I do as a service to the community. It's not about the paper or me, it's about doing the best I can to report the news of that community. To show readers something that they wouldn't see on their own. To take a different perspective of the ordinary. My interest in photojournalism developed out of my desire to be a part of history. In a small community, no one else is doing what you're doing. You are documenting events and news that would otherwise go unnoticed. Sure a lot of assignments are going to suck, but it comes down to attitude. It may sound corny, but I try to go in to every assignment with a positive attitude and make the best image I can. I've found that you have to take the good with the bad, and in the end hopefully you'll have mostly good.

:::BIO:::

Nathan Morgan is a graduate of Western Kentucky University's School of Photojournalism. He began his career at The Midland Daily News in Midland, Mich. where he worked as a staff photographer and photo editor. He is currently on staff at The Bowling Green Daily News in Bowling Green, Ky. Nathan is married to his high school sweetheart, Kelly, and is the proud father of two sons, Milo and Crosby.

You can view his website:

http://www.nathanmorganphoto.com

http://nathanmorgan.tumblr.com/

EDITOR'S NOTE:

This week's spotlight was done by a guest interviewer Sean Proctor. Proctor is a 2011 graduate of Central Michigan University and is currently a staff photographer at the Midland Daily News in Midland, Michigan. Before landing at the MDN he interned at the Jackson Citizen Patriot in Jackson, Michigan and The Virginian-Pilot, in Norfolk, Virginia. While in college, he was a multimedia intern at Denali National Park in Alaska. When he's not taking pictures of squirrels, Sean likes to enjoy a good craft beer. He's also a lover of good science fiction (in all mediums), and hopes to one day be appointed as Josiah Bartlet's presidential photographer.

You can view his work here:

If you wanted to be a guest interviewer and interview a photographer about a photograph, please contact Ross Taylor at: