Spotlight on Luke Raffety

Aug 21, 2015

TID:

Luke, thanks for being open to this. I loved this image when I saw it come across your news feed, and was curious to learn more about how you made it!

LUKE:

Of course! It’s an honor that you reached out to me, and I’m happy we could make this work.

This photo was created at 13,976 feet on the summit of Mauna Kea, which is located on the Island of Hawaii; the largest of eight islands that make up the state. I was traveling to Honolulu to visit some family, and was encouraged to travel and spend a day on the neighboring “Big Island” of Hawaii while out there. I bought flights, a rental car and a map. I did a little bit of research, but I like to go into such trips with as little of a plan as possible. When traveling like this, I like to be prepared, but not committed- I find life’s a bit more adventurous that way.

I was only on the island of Hawaii for one day. I spent most of that morning driving up and down mountains, and photographing the island’s multiple volcanoes. However, in the middle of the day the weather began to deteriorate so I adapted my plan. I had read about the summit of Mauna Kea and how it rises above the clouds and weather, almost always offering clear views of the sky – so I knew I had to go there. As I was driving up the mountain, I stopped and talked to a park ranger who explained that due to the height of the summit, most visitors would experience altitude sickness. “You’ll feel like you’re dying, and there’s nothing you can do about it,” he said as a matter of fact. I hadn’t been on the summit for 20 minutes before his words came true.

(examples of pressure differencial)

The altitude condition was certainly one of the most interesting, and challenging, issues I’ve run into while photographing. In all, I was on the summit for about 5 hours, and as time went on I began feeling worse. Despite the dizziness and headaches, I kept shooting the whole time. The summit had a completely clear sky, and you could see the clouds a few thousand feet below. The view was indescribable. I set up a few timelapses and started shooting. After the mesmerizing sunset, I prepared to start shooting the night sky. The summit of Mauna Kea is world renowned for its view of the night sky, and is home to 10 of the world’s largest telescopes (picture in the picture).

Unfortunately, I had to be off the mountain by 10pm, and ran into a few camera issues, but I was able to produce this image, along with some mighty timelapses, so overall I was very pleased with the final images and outcome of the trip.

TID:

This stemmed from personal work, can you talk about which you do often - especially in motion production. Can you talk about your preparation for this?

LUKE:

This photo was actually inspired by this photo:

I took this photo in Switzerland back in 2010. In 2010, I challenged myself to photograph the sunset everyday for 365 days straight. This was back in high school when I was getting into photography. I lived in a small village in the Swiss Alps that summer, and spent much of my time exploring the landscape photography. Long story short, it was always cloudy around sunset and I was getting fed up with cloudy sunset pictures, so one day I took a tram up this mountain and photographed the sunset from the summit (~10,000 feet). The tram stopped running before sunset, so I wound up sleeping the night on the summit. It was here I started experimenting with long exposures of the night sky. The next morning, I hiked down. It was that sunset and display of the stars that inspired me to go to the top of Mauna Kea last week.

I value personal work just the same as client work, or school work. Photography is photography, and should be done for yourself regardless. As a photographer, I can’t help but shoot when I travel. I try to capture the essence of a place as best I can. Whether it’s the people, the sights or the landscapes, it all defines a place. Personally, I find it easiest to accomplish this through video. It’s something I began doing while traveling a few years ago. While a few images can represent a place, I feel that a video (or a series of timelapses) can take you there in a whole new dimension. https://vimeo.com/134385172

(contact sheet from part of the time lapse)

As I alluded to, I don’t like to plan too much. I find it restricting in a way. I do research, compile lists and bring information, and then just play it by ear. For this trip, I made a list of places, drew a few dots and circles on a map and then set out to see it all for myself. The true spirit of my travel photography is to shoot what I see and what represents a place. You can’t plan that; you can only immerse yourself and shoot what you see. Last week, I got my rental car and just started driving. When I saw something that stood out, I would stop and just start shooting. While you may miss some things, I believe you find much more by just exploring.

On a technical level, I came prepared with my trusty camera backpack packed with my 5dmkiii and L-glass. I had more batteries than I could ever use (or so I thought), enough SD cards to shoot a feature length film, a tripod, an intervolometer and food and water for a day. I thought I could beat the altitude sickness just by eating and drinking water; it’s not that easy as it turns out.

TID:

Even with preparation, there’s always things that pop up that you have to problem solve for. When you arrived, what did you learn that was problematic that you didn’t for see?

LUKE:

Definitely! For me, that’s the fun of it in a way. I’m a problem solver. If things went to plan, this job wouldn’t be any fun. In this case, it was the altitude sickness. The park ranger’s words echoed through my head the entire time. I did, in fact, feel as if I was dying.

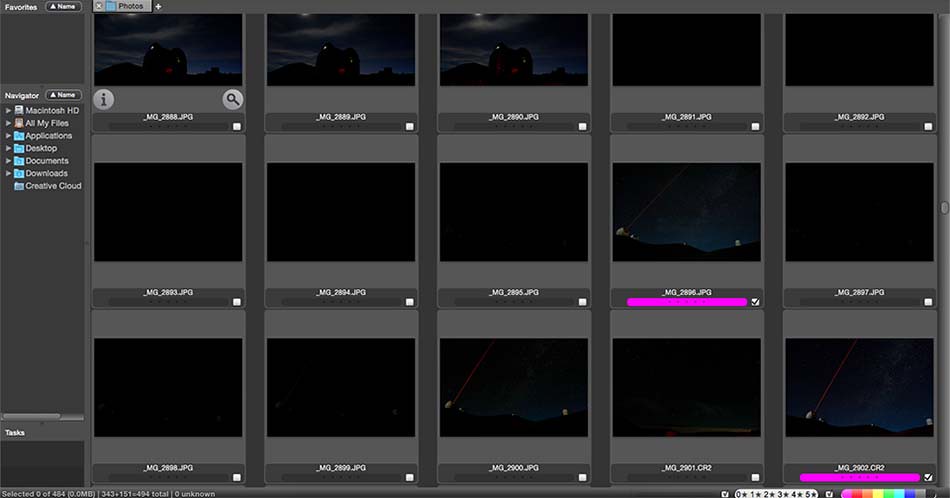

By the first hour, I could feel it. I felt dizzy, and like I had the worst headache I’ve ever had. By the end, I could feel my mental capacity being affected; simple mental computations were difficult. The weather was also another factor. I had packed a sweatshirt, but was wearing shorts and a t-shirt because after all it was Hawaii, right? Well, it was down at 40F by sunset, and kept getting colder once the sun was gone. Luckily I had my heated car to retreat to. While the altitude led to discomfort, I also believe it limited my ability to make proper calculations for the long exposures – why the contact sheet shows underexposed photos.

Another issue was with my equipment. As you know, a long exposure photo takes a bit of time to process in the camera before you can review it. Not thinking, I was shooting on one of my larger, but slower cards (writing speed). Because of that, after each 20-minute exposure, it took about 10-15 minutes to process. As you can see from my contact sheet, I was only able to get off a few shots before I needed to be off the mountain by the time the gate shut at 10pm, and I was unable to make the proper adjustments.

Honestly, the featured photo is “a failure” in a way. My goal when I set out was to make a long exposure shot of the stars moving and the telescopes in the foreground. But due to my faulty calculations and slow cards, I failed and that wasn’t an option. As a last ditch effort, I tried a shorter exposure with a higher ISO. And then, wow! When I reviewed the photo, I saw the telescopes laser and stars and how well they all worked. I had faintly seen the laser with my naked eye, but was unsure of how it would expose. Needless to say I was thrilled with the outcome of the shoot. The image I created was better than that which I set out to create.

TID:

How did you overcome these problems?

As explained above, I took a few deep breaths and thought about ways to fix said problems. Being patient and staying calm is key. Few problems can’t be fixed, and there’s nothing that adapting the final goal wouldn’t change. I’ve often found that changing my end goal has taken me to places I would’ve never gotten to otherwise. I’m not saying you should give up, but should be rationale and know to cut your loses and try something else, potentially better.

As the contact sheet showed, the shoot did not go as planned, but by adapting and being patient I created a stronger image.

All I can say is come prepared. That’s how I’ve been able to overcome most issues on shoots. Extra batteries, food and water and extra cards – it’s hard to have too much of those things on such a shoot.

TID:

What have you learned from this shoot?

LUKE:

The importance of adapting. As photographers we often strive to capture interesting and unique scenes. So, by very definition, we can only plan so much. We can plan subjects, styles and locations, but the moment and the true value of such an image can’t be planned. It’s spontaneous and needs to be found; that’s what makes it so special. We’re explorers and storytellers; we immerse ourselves in a land and then create images that tell/represent that place.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself in this shoot ?

LUKE:

I have a tenacious spirit. When I was on the summit, and feeling sick, the thought of coming down early never crossed my mind. For me, it wasn’t an option. I had started something and was determined to get photos of the night sky, so I stuck it out. While it’s important to balance that with responsible decision-making, I’ve learned that I am determined. The reward of looking at that photo on the back of the camera on that summit made it all worth it.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Please walk us through how you photographed it, and what was going on in your mind at the time. Also please discuss how you got in this position to make the frame.

LUKE:

I had rented a 4x4 Jeep which allowed me to drive to the summit. On the summit there were multiple dirt roads, connecting the telescopes and observatories. Before the sun set I drove around to every possible spot and looked at how the telescopes looked with the mountains, and imagined what the stars would look like. Knowing that the moon was going to be rising around 7pm, I made sure to include that light source in my calculations. I decided on two spots, and once the stars came out, I tried both.

I set up my 5dmkiii on my tripod and connected the intervolemeter (which allowed me to keep the shutter open for longer than 30 seconds). As I explained, I tried to do a few longer exposures (~20 minutes), but in the end wound up just going with a 1-minute exposure at a higher ISO. Another technical issue was focusing. I wanted the telescope/mountains to be in focus. The AF wasn’t working because it was too dark, and I was unable to manual focus as well. At one point a car drove by the telescope and I quickly manually focused on the headlights, and then made sure to keep it locked for the rest of the night.

I purposefully put the mountains and telescopes in the frame to add a sense of place, as well as scale in a way. Mauna Kea is well known for being home to those telescopes, so I thought it was only appropriate that they be in it. And honestly, the laser was just dumb luck. As the shutter was open I saw it, and wondered how it would expose. When I saw the final picture, I was amazed. I loved it.

TID:

You’re still in school, and early in your career, but what have you learned so far (using this shoot as an example)?

LUKE:

Although I’m a student, I don’t like to consider myself as a “student-photographer.” Yes, I’m still learning photography, but that’s never going to stop. That will never stop for any of us. I’ve worked hard to balance school, personal and client work over the past few years. I’ve been doing client work since sophomore year of high school, and am very intentional about when/where I mention being a student. Sometimes it gains traction, and other times you may lose credibility.

The world of photography and film are changing day by day. While the traditional age of photojournalism that was booming, say 50 years ago, is fading, new opportunities are being created. While the changes are overwhelming, so are the new opportunities. I can’t think of a more exciting time to enter into this industry than now.

Like anything in life, photography is what you make of it. I’ve learned that you get back what you put in. I’ve been proactive since Day 1, and have used photography as a vessel to travel the world, tell stories and experience life in a way I would have never been able to otherwise. When you look for opportunities, put yourself out there and take chances -- amazing things will happen.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers wanting to do this type of work?

LUKE:

Just get out there and shoot. It doesn’t matter what, it doesn’t matter if it’s going to win a Pulitzer, or not. Just the exercise of putting yourself out there and shooting is good enough.

As a travel photographer and filmmaker, I’ve always forced myself to document places I visit and record stories I hear no matter where I am. Whether I’m on vacation or traveling for a shoot, it’s an exercise to just get out there and do it.

You don’t need to go somewhere exotic to tell an interesting story or create a stunning landscape. I started doing my daily sunset project in 2010 to remind myself that. I found that when I was traveling I would always go out of my way to shoot the sunset, but I realized that the sunset, or any scene for that matter, can look just as beautiful in your own backyard. Throughout the project, I forced myself to find beauty in every sunset (even rainy ones), and regardless of the location.

Furthermore, be able to adapt and change. Next week I’m traveling to Haiti and Cuba to shoot two separate documentaries. It would be ignorant of me to assume that everything will go to plan. From language issues to camera problems to subjects falling through, not everything will go to plan. That’s intimidating to think of right now, but at the same time exciting. It’s exciting to figure out what will happen. What will change, what will develop and what might happen on a whim that I could have never planned. Stay tuned for those stories!

So, in short, go out there. Push yourself. Experiment. Try shooting some video, put together a timelapses, improve your photography or experiment with HDR… Don’t limit yourself, and go explore.

:::BIO:::

Luke Rafferty is a senior studying Photojournalism at the S.I Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Luke is an accomplished freelance photojournalist, and travel filmmaker. Luke’s film work has been recognized across the country, including by the Hearst Foundation.

Luke began his career as a photojournalist by freelancing breaking news in the Philadelphia region, but quickly discovered the full potential of photography, and began traveling to tell stories and create film content that told stories of culture and place. After graduating, Luke will continue to work as a freelance filmmaker.

Instagram: LukeRafferty

Travel Blog: https://lukeraffertytravels.wordpress.com/

Website: LukeRaffertyVisuals.com