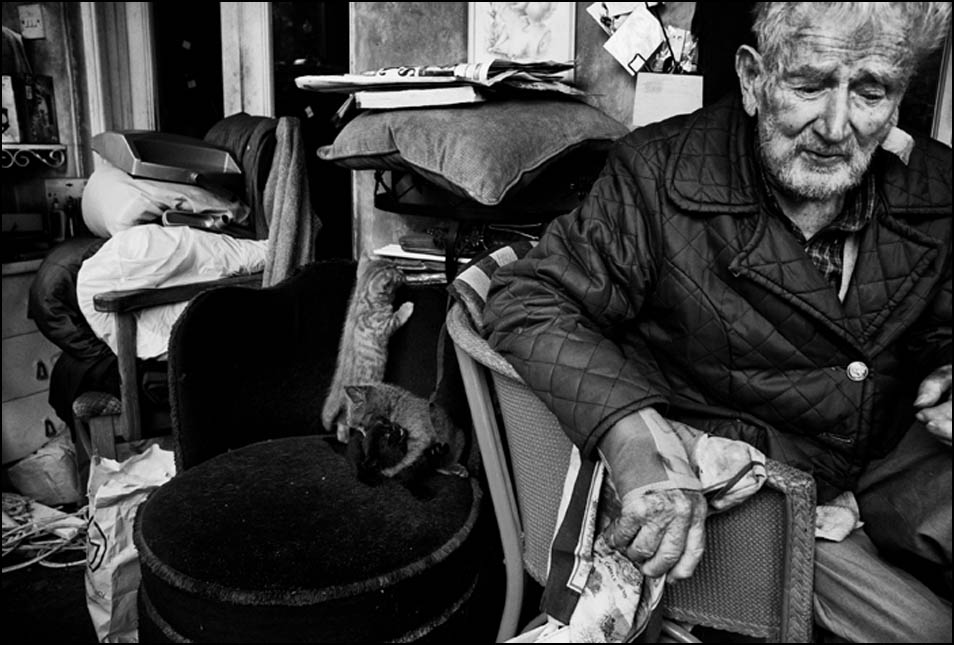

Spotlight on Jim Mortram

Mar 20, 2012

TID:

Thanks for sharing this image, please tell us the backstory of the picture.

JIM:

The long-term project is about small town inertia - why people become static in a place they all hate... yet never leave. This includes hearing the personal stories of those on the fringes of the Market Town, Dereham, UK. The pictures are of those marginalized in the local society. I usually try to catch up with everyone I shoot at least once every month. This was just another occasion where I came by to talk and photograph one of the people I document.

This image is of a man diagnosed (at 17, he's 41 now) with schizoid obsessive behavior. He's locked into an introspective world whereby he obsessively remembers the minutiae of his life (most of which our memory disposes of). He remembers random sentences and the smallest of events. He becomes consumed as they loop continuously within his conscious thoughts. He has a history of sexual abuse, as well as misdiagnosis of prescription drugs. All of these collectively have exiled him from a normal life.

He's very isolated, lives alone and smokes obsessively - something he is concerned about, but it's a habit he is unable to break. It's a lot like the unstoppable compulsion to dissect and replay old memories. He tries to combat both the loneliness and illness with his art and poetry. I often tell him 'You're the new Basquiat', and I mean it. His paintings are a true representation of every memory, every message, every prediction and mood he's ever had.

TID:

Why did you start taking pictures?

JIM:

A few years ago I'd become quite insular myself. Working as a caregiver in my family home; it's a intense situation, quite highly stressed, with odd hours. Before you're even aware of it, the ties you once had - friends and the connection to the outside word - erode. It's a subtle shift, and by the time I noticed it was too late to cease that evolution.

I was loaned a camera by a friend and immediately knew I had to document people. The challenge was where and how. I live in a very rural, low-population part of East Anglia, UK; I was tied to my duties as a caregiver. Long periods away from home to shoot were out of the question. I hated the situation. I wanted to escape, but there was no way that was going to happen.

One relationship really helped pull me out of my shell and pull my photography into focus. It was because of a person close to me, 2 doors from the family home, in fact. I'd known W.H. since I was a child. In his late 80's, I would visit often to hear his stories (pictured above). Gradually I began to make portraits. He encouraged me greatly. The whole process was very organic and instinctive.

He became ill with cancer, and I ended up being one of the last people to talk with him - certainly the last to photograph him. This experience really forged the understanding of why I had to document local people. I began to understand that everyone has a story; that they are all important.

It also made me reappraise my location and my relationship to it. I finally harmonized with where I lived. Where I had felt suffocated suddenly transformed into a place that was of the highest importance: Dereham, one of those small forgotten towns, with a distinct strata of the population that have also been forgotten.

TID:

How do you approach people you photograph?

JIM:

At the start, I would just walk up to strangers and ask. I would explain what I am attempting to do, why I'm doing it, and take it from there. All people I photograph are strangers.

TID:

How do you handle it when people say no?

JIM:

Thankfully, that's never happened. Though if it does, that's OK with me. It is a choice for them to make, and I would respect that. Without the consent, no trust could grow. Without trust, no relationship would be strong enough for me to get close enough to make images I'm aiming to get.

TID:

You said you spend time with strangers, does it ever feel strange photographing people you don't know that well?

JIM:

No, it's never felt strange. It's my honor to listen. I live for it. I know: without the bravery and trust of people, I'd never make a photo. I'm always indebted, and I always share this with everyone I shoot. One hundred percent of the time when I take photos we are conversing. I'll ask a lot of questions, then listen. Many of the people I document have no one in their life that's interested in them, no one to listen. For many it's a release, a cathartic experience. I can relate to that. When the stresses of being a caregiver got to me a few years back, I went without speaking a word aloud for 7 months. I appreciate these chances to communicate very much, and I make as much of an effort as I can to relate to the stories that I am told. There's a real bond of trust that has to be earned.

TID:

How do people react to the pictures you take of them?

JIM:

I've never had a negative response. I always keep people up to date with everything that happens to images: I make prints and give them away, every time, when work is published. I always make sure a copy is there to give too. The reactions, especially when the photograph was taken within an intense moment, garner the greatest reaction I feel. My own view is that it's therapeutic for the people I am documenting. It's often like documenting a confessional. People often tell me it's a release for them, and these shoots feel like collaborations. Cathartic collaborations.

TID:

How do you think your work has changed you?

JIM:

I don't think photography has changed me in relation to the people I photograph in any way. It's for sure consolidated many elements within me, though. Photography has literally been the lens that I was able to focus myself. It's been my facilitator and a saviour in many ways, and very much continues to be. I never entered into image making to reap the benefits, nor to make art. I was, however, very set on documenting and recording the people around me that I felt were marginalized, overlooked and adrift. For me, that's pretty much everyone I encounter, including myself.

The key for me was not to objectify, nor to over dramatise and never to exploit. There's a great gift and grace in one's being granted permission into their reality. It's trust that gives permission, and it's also the key that unlocks it. I work under the well-used adage: treat those around you as you wish to be treated.

I'm very inclusive in my shoots and stories. The people I document and make portraits with are very aware of our interaction. They're aware that it's their story, and aware that they can trust me to account for their situation.

TID:

Ok, lets talk about the image. Tell us what was going on in the moments

around the picture, and why you were taking them.

JIM:

I know what to expect when I go to shoot Tilney 1 (his artistic name). Often he'll run me through the cyclic memories that have been plaguing him, the maps he's weaved linking cultural and personal events, as well as predictions and his inner fight dealing with his diagnosis and his loneliness.

This time was compounded by a succession of sleepless nights for him. His condition often swells and reaches a point of critical mass where he becomes overwhelmed. The moment of this shot was during a long monologue where he was describing this point. He also opened up for the first time about being abused sexually as a child. The burden of everything at this moment became a release. It visibly overcame him and his gesture echoed this moment.

TID:

Have you shown him this picture, and if so, what does he think about it?

JIM:

Yes. He loved that it depicted the real situation he's in and the moment of his expression. You can see the world he's within. You can see his creativity in the artwork scattered around him.

TID:

What has surprised you, what have you learned from the people you photograph?

JIM:

What I've learned, time and time again, is that people who live outside accepted social norms show a very common, very human, humble vein of kindness, selflessness and resolve. It also places a pressure from society leading to the fringe of a slow death and erosion of personhood.

I've learned that the strength it takes to battle on through this is awesome. People with nothing have such resilience. Their appreciation of momentary joy is profound, especially when much of their life is suffocated by loss, loneliness and everyday battles.

I set out to document those who are marginalized - fractured from the rest of the society around me - and I found the most incredible collection of people. People who are damaged by life, but in many ways are more "human" because of their experiences. These are not people whose identities have been subdued by consumerism, anesthetized by popular culture. They are, in fact, the contrary.

In spite of the pain, suffering, loneliness and prejudice, I am ever more aware that the people I document are the most alive and the most human of all.

TID:

In the end, what have you learned about yourself?

JIM:

Everything. It's helped me through a lot, personally, and taken me to a place within myself where I overcame a lot of personal demons, something which I never could have foreseen. It took me out of myself, taught me to listen more, see more, search more, sacrifice more and give more. Though I don't make these images for money for sure it's been the single most rewarding element of my life outside of my family and now, my community.

BIO :

Twitter : https://twitter.com/#!/JAMortram

Next week on TID we'll turn the table on editor at large Mike Davis

and interview him about this image:

If you have any suggestions or if you want to interview someone

for the blog, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting.