Spotlight on James Chance

Jul 9, 2012

TID:

What a powerful image. Please tell us a little of the backstory.

JAMES:

The image was shot during a funeral in Manila’s North Cemetery and is part of a larger body of work documenting the community that live and work there. This was a typical Catholic funeral with an open casket. Family members and friends are given time to grieve, say their final goodbyes and sometimes place mementos and notes in the coffin before it is taken for burial. The inclusion of a priest is a little uncommon. It may be that this particular family is a little wealthier than the majority of people who bury their dead in this public cemetery. This was the first time I had seen a religious figure in full attire preside over a ceremony.

TID:

This is part of a larger body of work, can you tell us about the project?

JAMES:

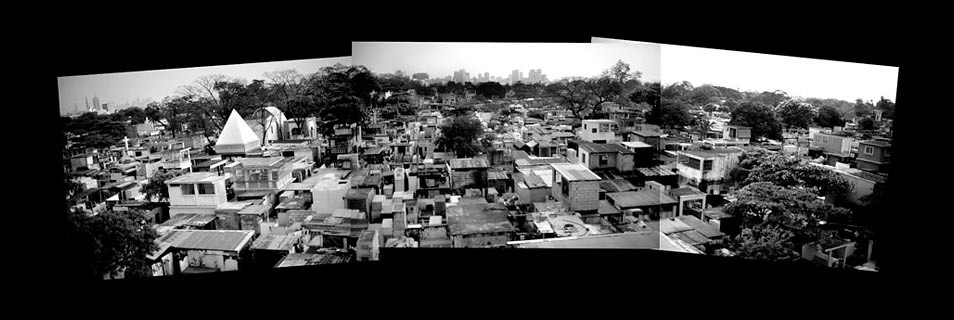

I have been working on a long-term photography project documenting the community living in the cemetery since 2008. The North Cemetery is the city's largest Catholic cemetery and besides providing a final resting place for hundreds of thousands of the city's Catholic dead, it is also home to a living community of more then 2,000 people.

Manila, Phillipines is the most densely populated city on the planet. Overcrowding and poverty have resulted in people inhabiting this surreal location; they have been there for generations now. Despite the lack of infrastructure and typical housing, the cemetery does offer many practical advantages, most significantly a source of income. Many of the residents earn a wage through various vocations specific to the cemetery. For example, caretakers will receive a wage (from the family that owns the plot) to maintain and protect one or more mausoleums. Other sources of income include assisting with burials and exhumations and building new tombs. The cemetery residents serve all aspects of this micro-economy.

As a whole the project seeks to illustrate the larger issues of poverty and overpopulation and how they affect communities, families and individuals. I hope this work will provide insight into how the community has adapted to living in this unique environment. On a personal level, I had been interested in how we as humans adapt to different environments and how we make a place our home. I think what excited me most about documenting the cemetery was the beautiful, ironic contrast of teeming life in a place typically devoid of such, and normally associated with death and emptiness.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working on this project?

JAMES:

Initially access to the cemetery was the biggest problem to overcome. When I arrived for the first time with my wife Jessica to start the project we were turned away. There is a security team that patrols the grounds and even though this is a public cemetery, foreigners are not allowed to enter without permission from City Hall. After that, I am happy to say challenges have been few and minor. I guess good light has often posed an issue, as Manila is often very overcast and cloudy.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

JAMES:

We went to City Hall and applied for permission to enter and photograph inside the cemetery. After a week of visiting countless desks in numerous departments we obtained official permission to enter. It felt like it took forever because it was eating into the time we had available to shoot, but we got there in the end. Bureaucracy is always something to behold!

As for light, this was the initial reason I chose to work in black and white; during my first visit I saw maybe 3-4 days of sunshine. I quickly embraced the black and white aesthetic feel it makes sense in the environment. I have also shot a lot of film on this project and have modified cameras and lenses to yield “rougher” results, again, I feel this better represents the place.

TID:

How did you work mentally to gain access?

JAMES:

The initial issues gaining access to the cemetery were purely official. We just needed paperwork to get through the gate. This was unexpected and a hassle to obtain, but once we had it we knew things weren't a complete loss. One problem I had with the official permission though is that I had to be escorted by one of the security guards for the whole time I was on the grounds. I guess at first this was in some respects useful, it meant I had a kind of tour guide and could learn the location, but when it came to settling in to the photography and spending time with people it was rather prohibitive. I think we all like to work alone. I want to be able to engage with my subjects with no distractions. Having a uniformed security guard on my shoulder was definitely a distraction. However, this was the only way it would work at that time, so it had to be dealt with. I was able to develop good relationships with a few of the guards and this has proved hugely important throughout the project.

During this first trip I was introduced to Jerry Juan and his partner Jenny. Jerry is seen as the "Don" of the cemetery and commands huge respect from the residents. I spent a lot of time with Jerry, Jenny and their family and they have become good friends. They are an interesting example as they have built their own home inside the cemetery and run two businesses (breeding exotic birds and renting tricycle taxis). I have been working with them the whole time. My relationship with Jerry now ensures my safety in the cemetery, so on subsequent trips now knowing the guards and them knowing I am with Jerry, I have been able to avoid the permission slip. Again: relationships, relationships, relationships.

So now I have been able to work freely. On some of the earlier days I would have a "helper" (one of Jerry's understudies) who would tag along at Jenny's request to make sure I was safe. To be honest, people have always worried more about me than I have about myself. I don't mean to sound blasé, it's just in the many weeks I have spent, I have never had reason to fear my own safety. There are rougher areas, there is drug abuse and the cemetery areas are known as a hideout for criminals - but this is just like any community. If you go into those areas, don't go alone and watch your back. Common sense.

So once I was able to work on my own I would do circuits of the areas that interested me. I would arrive, walk up the main avenue then just circle around. At first I would get many strange looks, but every so often someone would smile and wave. Everyday I take snapshots of people and bring them prints the following day. This is a great way to build relationships with people. Obviously language is often an issue, but most Filipinos speak a little English or have a friend who does. I have also picked up a little Tagalog. Either way its amazing how much you can communicate with zero skills. Being a Brit I always talk about the weather.

Many of the residents enjoy a drink, so I would often be offered beer or liquor. In this case I would certainly take the time to sit down and drink and share cigarettes. In 90º+ heat things can get a little sketchy though, so knowing one's limits is important! The community is very tight, so once you have made friends with a few people word gets around that "that guy's OK." So I would do my rounds, hand out pictures, say hi to some, sit with others... until it all just became very normal.

Another good friend in the cemetery is Steve Cabuso. He speaks English well so he has been a massive help in educating me about the place. I sometimes hire him as a fixer if he has no work on a particular day. It's not so much that I need it, I just want to give back. When I am with Steve I will use the opportunity to communicate more with others who don't speak any English.

So in time I have been able to blend in. I mean I still stick out like a sore thumb, but the residents are my friends. They know my name and shout it out when they see me. I feel very trusted within the community now.

TID:

Now onto the photograph. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

JAMES:

At this point in the project I was focusing on “work” in the cemetery and more specifically the work centered around funerals. Cemetery residents earn money by assisting the undertakers (who organize the funeral procession), by carrying the coffin to its burial site, and sealing the tomb.

It is important to understand how densely packed the cemetery is with graves. In the public areas, the tombs line up against each other and in many cases are stacked two or three high. This means the only way to get around is to step from tomb to tomb. The residents who assist as pallbearers have been navigating the tombs since they were children and know every area of the cemetery intimately. Even if the undertakers and family are able to locate the burial spot in the maze of tombs and mausoleums, physically carrying the coffin there would be extremely difficult.

One of the larger public areas has three roads intersecting on one side, which forms an open space. This area is often used to park the hearses and jeepneys (small public buses) that transport the funeral procession and to set up the casket for the funeral ceremony. I knew if I waited at this spot there would be a funeral arriving soon.

This wasn’t the first funeral I had shot in the cemetery, so I had a pretty good idea of what to expect from the situation. I have never had anybody object to my photographing a funeral there, in fact people have actually thanked me and shaken my hand, asked for pictures, etc. However, even with this knowledge I still check myself as it does feel so strange to be photographing strangers in such an emotional and personal situation. In this respect the main thing going through my head is not to offend anyone. After that I am scoping the best position to shoot from and how to get there.

As for the lead up to the picture, I always take a very noticeable spot early on and stand and watch for awhile with my camera easily visible. I want to be seen - it's not hard, I stick out like a sore thumb being taller and having fairer hair!

It is important to understand that due to the location and cultural differences, this situation is very different to how a westerner might perceive a funeral. For a start there are usually cemetery residents just hanging out and kids who clamber to get a look at the dead body, or are just playing amongst the tombs. The residents and kids (and often the peripheral attendees) laugh and converse and shout during as the relatives mourn. It is a VERY public affair.

So after making my presence known, I will move into the group and start to photograph the situation, getting ever closer to the casket and the family. Things can even be a little physical as people push back and forth to view the deceased. It’s not dissimilar to working in a press pack, so sometimes I find myself having to jockey for position a little. So in this strange, deeply emotional, yet very open and public affair, I work to photograph the family as they say farewell to their loved one.

In this image (I’m guessing) it is the deceased’s wife and granddaughter that mourn at the head of the casket. They were certainly the most emotional in the group and were being supported by their family members. As the young female reached out in her grief I was able to capture the frame.

As the casket lid is closed it is time to retreat back to the burial area as the residents will be carrying the coffin over the tombs to its final resting place. Actually, it isn’t the deceased’s final resting place. Due to the fact that the cemetery has no more space to accommodate permanent burials and many family can’t afford a permanent spot, tombs are rented for five years, after which the body will have decomposed and the bones can be removed and placed in a smaller tomb to make way for the newly dead. Once again it is cemetery residents who will open the tomb and perform the exhumation.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment that you weren't expecting?

JAMES:

Again, it's the fact that people are so understanding - or just simply don’t care about my presence. In many cases it can even become rather awkward as people will wave and shout to me, or take my photograph with their cell phone, all while the family is mourning, which is very uncomfortable.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

JAMES:

I think I have learned a lot about my own personality and how I interact the people I am photographing. It is about respect and sharing; for me it’s more about the relationships than the images. Once the relationships are there, the image-making is the easy part. Relationships are key. I learned early on to spend a lot of time, especially at the start of projects, just hanging out, not taking any photographs - usually drinking and smoking. Sharing cigarettes and alcohol is a great way to get to know people!

We never fully know how people will react to our presence as photographers. In this respect I believe we need to be very honest and upfront about our reason for being there. This doesn’t mean I need to verbally announce myself, but I let people see me and my camera so they can figure it out for themselves.

When in the process of photographing, especially with people you haven’t met yet, a lot comes down to how you carry yourself. Despite language and cultural differences we all communicate on the same basic levels. Body language is huge in this regard. Calm confident is key. Respect for the subject is hugely important, so eye contact, a smile, simply acknowledging their presence (and your own) in any situation is important. I never really try to sneak around shooting off the hip. I like people to know I am there as a photographer and don't have anything to hide.

I don’t get into tech talk too much, but small cameras make such a difference as one can be so much more intimate and move freely in a situation. (And they save your back!) In this respect I do find video a little more challenging because the equipment is larger and it forces me to work in a different way.

:::BIO:::

In 2009 James founded Chance Multimedia with his wife Jessica Chance. Chance Multimedia produces photo and video content for foundations, nonprofit organizations and commercial businesses. Chance Multimedia are producing a documentary film on the North Cemetery, which is currently being featured on Emphas.is: http://www.emphas.is/web/guest/discoverprojects?projectID=686