Spotlight on Danielle Villasana

Aug 23, 2015

TID: Hello Danielle. This is quite a moving image. Can you tell us about its context, background, and how you came to be there?

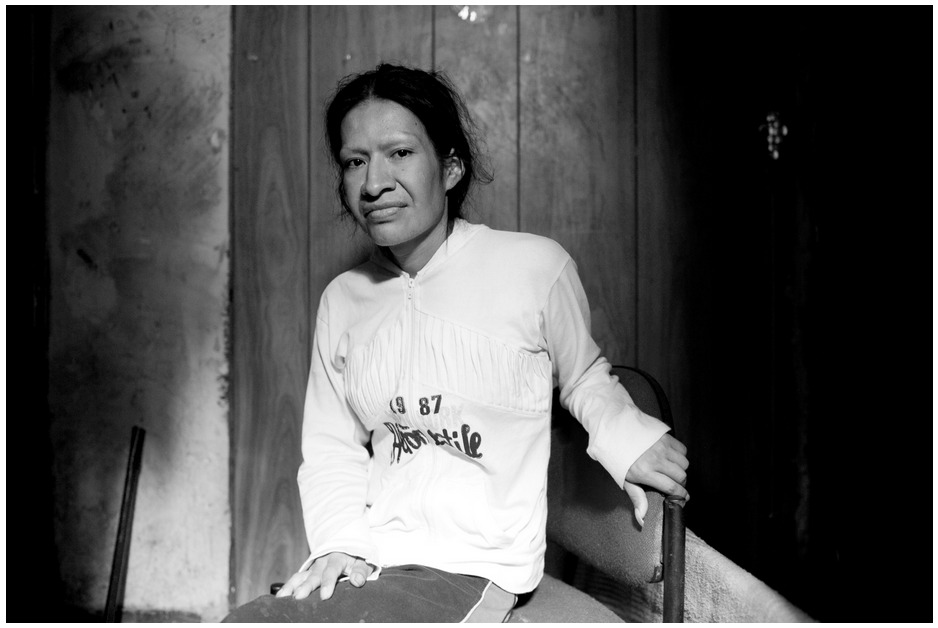

Danielle: I took this photograph after hearing the news that a Colombian transgender woman had been shot on the street by a police officer during a nightly raid. Though prostitution is not illegal in Peru, police officers will harass transgender sex workers, often taking them into custody without reason. After being verbally harassed by two cops, a woman Karen was with threw a rock at the police car. When Karen turned to run, an officer shot her in the stomach. When I heard the news, I contacted people in the journalism and medical communities to figure out which hospital she was in. As I knew she was Colombian, I assumed she didn’t have any family here in Lima to help her (even if she did have family, it’s very common for transgender women to be estranged from family). So, I knew it was important to figure out what the situation was.

Danielle: With the help of a doctor, I got into the waiting room outside the surgery ward. After waiting hours, finally a nurse allowed me to peek into the surgery room to speak with Karen. I quickly told her that I was there to help and asked if she needed me to contact anyone in her family. Thankfully, her brother had traveled to Peru and her mother was on the way. Thankfully Karen has such strong support from her family as it's very rare among the transgender community here. After purchasing some medicine she needed, I went home, telling her I would be back the next day. As an aside, the public health system in Peru - while free - can be quite frustrating in the sense that if a patient needs something and there is no family to buy it, oftentimes the patient will go without.

This photograph was taken on the day her mother arrived from Colombia. In my visits with Karen, she told me that her mom was everything to her and she was anxiety-ridden awaiting her arrival.

TID: Can you describe what was going on in your mind as the image took shape, and then also what you were thinking when you made the image?

Danielle: I was quite nervous because I knew the moment between Karen and her mom was going to be very intimate and emotional. Though I knew Karen and her brother had mentioned me to her mom, I had no idea what to expect. Was she going to be hesitant with my presence, would she not want her photograph taken, was she going to be upset with my reaching out to Karen, etc.? When I’m nervous I try to mentally calm myself down and tell myself to focus. I also knew that the moment would probably be fast and I wouldn’t have time to adjust settings, so in those moments I try to make sure everything is ready to go beforehand.

When her mom arrived, Karen immediately started crying and it was a very intense moment for them. I tried to stay as separate and unobtrusive as possible as I knew that this was their moment. I tried to let everything flow naturally, only taking pictures when I felt it was appropriate. This photograph happened a while into her mother’s visit. Her mother didn’t cry right away. Only as things settled in and Karen recounted the evening did she break down into tears.

I realized right away that the moment of them embracing was really special for many reasons. One, it shows their incredibly tight bond and relationship, which again, is quite rare for transgender women with respect to family. Two, it took place against the backdrop of Karen being unjustly shot by law enforcement, which reveals the violence and danger that many transgender women face. Her mom was really receptive and very appreciative that I had reached out to Karen, so all in all I was quite thankful to have been able to document this moment.

TID: What were some problems or challenges you encountered during the coverage of this event, and how did you handle them?

Danielle: I’m quite hesitant to bring this point up because it’s one that I struggled with ethically, but photographing in hospitals in Peru is generally not allowed. Perhaps in some cases it’s allowed but as with most processes here, it would have undoubtedly taken forever to even get a “no.” As I had had a lot of experience with hospitals this year (at the same time I had been photographing a transgender woman who was fighting AIDS and Tuberculosis), I knew that the likelihood of getting authorization was extremely low.

Ultimately, I decided that because I wasn’t documenting anything to do with the hospitals themselves, i.e. not revealing malpractice or bringing any attention to the hospital, I decided in favor of doing so as the hospitals were merely a background to a larger story. I also decided that the benefit of seeing these images outweighed the potential backlash. Since then I have showed these images to health workers and will be using my project to help train medical staff on transgenderism so I think it’s safe to say that I made the right decision.

That being said, photographing was difficult because I didn’t want to flaunt that I had a camera. I had to be careful about when to take out, had to make sure all the settings were correct before doing so and could only keep it out for a few minutes at a time. I seriously started to feel like a ninja. On a positive note, these limitations really helped me think about composition and prepare for moments before they happened. I also really appreciated that I could put my camera in silent mode.

TID: Was there anything that you learned or put to use in later assignments that come about from this experience?

Danielle: Throughout my time documenting these women’s lives, the biggest lesson I have learned and put into practice time and time again is that you have to build trust first. When I started this project in 2013, I remember visiting the neighborhood where many live and work for months before even taking a photograph. Some nights I would just sit and talk to them. I was always very clear about why I was there and that I was a photographer, but it wasn’t until after a few months that I finally starting photographing on the streets and in their homes. For half a year, I also lived in their neighborhood, which proved fundamental to maintaining our trust and bond. Trust is something that you can gain, but it’s also something that you have to maintain. There are just as many times I have taken photographs as times I have not, if not more. So, trust, respect and patience are number one, always. From there I think everything else comes naturally.

Danielle: With respect to Karen, I actually didn’t photograph very often throughout her recovery process but I would visit her as much as I could. As I mentioned, I was also documenting another woman’s story at the time, which really occupied a lot of my time and mental energy. Also, in the other woman’s case, she barely had anybody to support her. Thankfully Karen did have the support and 24/7 attention of her mom, who lived in the hospital during her recovery.

I also want to mention that being able to intimately see how the health system works in Peru, especially with respect to transgender women, has motivated me even more to build relationships with people outside the journalism world. I feel very thankful that these women’s stories are gaining more attention, but I would say that this project has been pivotal for me in that it helped me realize in order to make real impact it’s necessary to partner and collaborate with other entities. Together we can be more powerful. So, over the years documenting this issue I have built relationships with NGOs, activists, researchers and health workers. For example, I’m currently assisting in bringing transgender women to a nearby hospital for free HIV testing, we are planning a health campaign and as mentioned before, my project will be used as a training tool for medical staff.

TID: How did you get into covering transgender issues?

Danielle: I became interested in LGBTQI issues when I was still a student at the University of Texas in my home state. At that time, the federal Defense of Marriage Act was still in place and politically Texas remains discriminatory towards LGBTQI people and their rights. For a multimedia class in 2011, I documented four LGBTQI families raising children in order to combat the idea that LGBTQI people are unfit parents.

One of the stories was about Nikki Araguz, a transgender woman who became an "accidental activist" when she was sued by her late husband's mother and ex-wife for Nikki's portion of death benefits after he died fighting a fire (and of course she was never allowed to spend time with her two stepsons again.) Though they were legally married, their marriage was invalidated in court based on the fact that Nikki at that time had not undergone sexual reassignment surgery (same-sex marriage at the time was illegal in Texas.) So, long story short, during my time with her, Nikki really opened my eyes on transgenderism and I learned so much.

The following summer, I received a grant through UT to document the Gender Identity Laws passed by Argentina in 2012, which to date are the world's most progressive laws with respect to gender identity. I spent three months following the lives of three transgender people and my eyes were opened even more.

So, when I moved to Peru the following year in 2013 to finish my last semester as a senior studying abroad, it was a very natural desire to see what life is like for transgender women here. Again, my eyes were opened even more and of course I was quite shocked by the reality they face here in Peru.

TID: This statement you made particularly struck me: "So, trust, respect and patience are number one, always. From there I think everything else comes naturally." Can you talk about how you work to gain trust and respect?

Danielle: This is a good question and I believe there are many layers to trust and respect. As a photographer who also does assignment work, you oftentimes have to work quickly with respect to helping people feel comfortable with you and the camera. I really like to get to know people, so I open up really fast. I'm really extroverted so it's not too hard for me to do that. I don't often take images where the person being photographed doesn't know I'm there. Maybe I could be criticized for that, but I really like to get close to people, it's just who I am and it's one of my most favorite aspects of photography.

That being said, I feel like there are layers that start to peel away the more time you spend with someone, the more you understand each other, the more you trust each other, the more you open to each other. With respect to working with trans women in Lima, because they are a community of people that have suffered so much rejection and discrimination on so many levels, I knew it was extremely important for me to work slowly and to build trust over time. There is a lot of violence, a lot of substance abuse, a lot of emotional trauma, and those are just simply not things you can expect people to immediately show you or trust to witness. So again, I spent the first few months just getting to know the women, spending time talking with them on the streets and slowly, very slowly, began visiting them in their homes. I also lived in the same neighborhood as them for half a year and that's when I would say I really became part of the community. I'm welcome in their homes, I am friends with many of them on Facebook, I talk to a lot of them on the phone or text message, it's just like I'm part of the community.

Danielle: Another point about building trust and respect, I believe that when you truly care about someone or an issue, people see that. There have been just as many times I have photographed their lives as times I have not, perhaps more, when I'll just spend time with them, going out for lunch, to a doctor's appointment, shopping at the market, etc. They know that I'm there for them besides just to photograph, they know that I would drop almost anything if they needed me.

Lastly, I believe the trust you build with someone you are photographing is a really sacred thing and you have to be careful not to break it. If you truly care about someone, I think it's really hard for that to happen. Building deep levels of intimacy takes a lot of time and a lot of energy, but it's extremely rewarding and fulfilling to be entrusted by these women, to build friendships with them and to feel like I'm doing my part to battle alongside them.

TID: Can you discuss what "patience" to you is, and how you cultivate it? How it is utilized in your work?

Danielle: Well again, there are just certain situations you simply cannot rush into. You are entering people's lives as an outsider and it takes time for both parties to feel comfortable with that, especially in situations where the person has suffered through so much. To build on my previous answer, the more time I spend with them, the more I feel they allow me to see. There was so much I heard about but never saw--the violence, drug abuse, etc.--and it wasn't until I had truly built layers of trust with them that those realities I had always heard about I began to finally see.

TID: Can you discuss the emotional aspects in this story - how you've dealt with witnessing such heavy and emotional journeys?

Danielle: This is another great question. As photojournalists, I believe we often put ourselves in really intense situations because of a desire to help bring visibility to people who are often mistreated by society. Again, personally speaking, I believe it's important to really understand someone and I get really close, which oftentimes means people's pain or emotions also really touch me on a deep level.

Danielle: For example, earlier this year I met Piojo, a trans woman fighting AIDS and Tuberculosis. I was introduced to Piojo by Tamara, the first woman I met and the person I'm closest to in the community. That was a really intense time for me as I spent nearly every day with Piojo, helping to navigate the extremely complicated and stress-inducing public health system here in Peru. My time with Piojo is a whole other story, but I guess to answer this question, when she passed away in March it was extremely painful for me. I had been somewhat preparing myself for her passing as many doctors had been very blunt with me about the likelihood of her surviving, but it was still really hard. The one consolation for me was that I had helped reunite her with her adoptive parents who had really treated her badly as a child and teenager (which ultimately led to her running away from home at a young age, an extremely common story among transwomen worldwide and what cause many of them to fall into prostitution). When they reconnected, her parents really opened up to her identity and started to make a real effort to accept her. So, at the very least, I hope that Piojo was able to pass with some feeling of peace. Though it still makes me sick to think about the fear that she faced and the feeling of helplessness--she was really young, only 30 years old. Sadly, what Piojo went through is not uncommon as 30% of trans women in Lima are infected with HIV. And, just like Piojo, many wait until it's too late to seek help due to discrimination on so many levels.

Danielle: So yes, being close to these women and witnessing the pain they undergo can be really intense but you just have to be strong. When I feel overwhelmed or mad at the world or frustrated or helpless, I try to re-focus on the small things--the small steps I'm trying to take, the moments of happiness I share with them, the little victories like helping a woman get on HIV medication, educating my friends and strangers here about transgenderism, being a shoulder to cry on, or a friend to go dancing with. Despite all the darkness there is also a lot of light, we have a lot of fun together and in the end I feel good knowing that they know there is someone who believes in them, who supports them and who is fighting with them.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Before double-majoring in photojournalism and Spanish at the University of Texas, Danielle traveled through more than thirty countries in Europe and West Africa, photographing along the way. After meeting a photojournalist in Ghana, she realized that photography combined with discovery, cross-cultural communication and a desire to spread awareness about global issues equates to journalism. A lightbulb went off and she quickly headed back home to begin her studies.

In 2014, Danielle co-founded Everyday Latin America on Instagram, which is part of the Everyday community founded by Peter DiCampo and Austin Merrill as a way to combat stereotypes in the media.

"A Light Inside," Danielle's long-term project on transgender women in Lima recently won the Magnum Foundation's Inge Morath Award and was recognized by the Pride Photo Award contest. Danielle will be collaborating with UN AIDS and other local organizations at the end of the year in a public photography exhibition of medium format portraits of transgender people as part of the UN Secretary General's Free and Equal Campaign. A part of the Inge Morath funds will be used to make the exhibit possible.

Most importantly, Danielle lives and works by the advice of her mentor Donna De Cesare: "You are a human being first and a journalist second."

Danielle is currently based in Lima, Peru.

www.daniellevillasana.com

Instagram/Twitter: @davillasana