Spotlight on Dana Romanoff

Feb 17, 2016

TID:

Thanks for being open to this, Dana, can you tell the backstory of the image?

DANA:

“In much of the world, the most dangerous thing a woman can do is become pregnant” (Nicholas Kristof, New York Times, February 6, 2014).

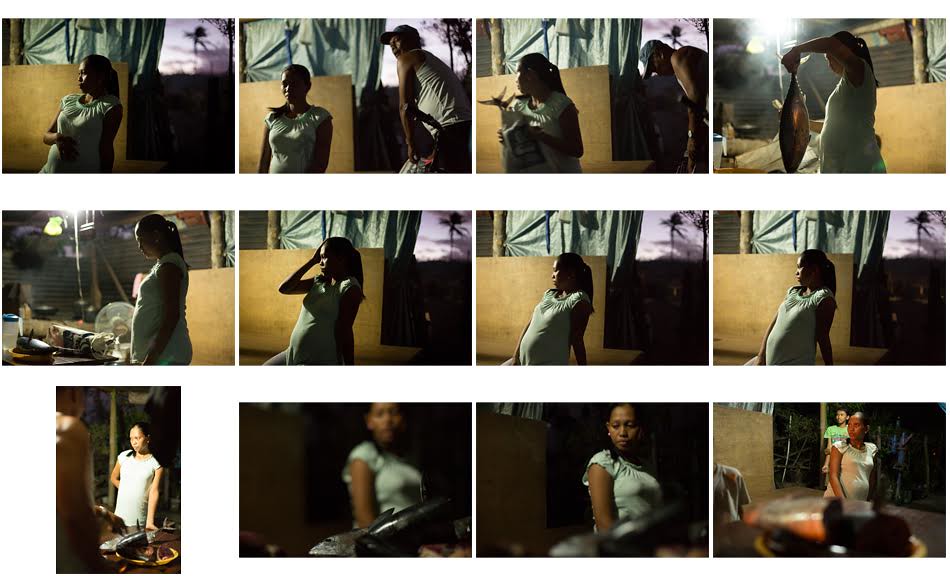

Arabelle is 20 years old and expecting her first child. The baby’s father died in Typhoon Haiyan, the largest storm to ever hit landfall, destroying the central Philippine islands in November 2013. Arabelle clung to the top of a coconut tree to save herself and the baby in her belly. She lives with her 10 siblings and parents in a tiny home that was destroyed by the storm. Arabelle will give birth at Bumi Wadah, a non-profit birthing clinic established after the storm by internationally recognized midwife Robin Lim to provide free pre-natal and maternity care.

Nearly 300,000 women worldwide die each year from complications during pregnancy or childbirth, 99 percent of them in developing countries. They die because there is no medical care for them, or it is too expensive. The United Nations has declared better maternal health as one of its Millennium Development Goals. Robin Lim is working to change these conditions. CNN’s 2011 Hero of the Year, Ms. Lim serves the poor and medically disenfranchised and committed to changing the world one gentle birth at a time.

Months after the storm in the Philippines the disaster was not over. Millions of women and girls of reproductive age were still in need of urgent care and protection. And over 800 women, often malnourished and suffering dehydration, high blood pressure, extreme trauma, inadequate shelter and lack of transportation were giving birth every day. There was limited or no access to emergency obstetric care.

Shortly after the typhoon, Ms. Lim went to the outskirts of Tacloban City in the Visayas, one of the areas hardest hit by the typhoon, to provide desperately needed medical and obstetric services to women in the affected area. Under a canvas tent, on the grounds of a destroyed elementary school, a clinic named Bumi Wadah was erected. Ms. Lim, along with five local midwives and a rotation of foreign midwives and healers, offered free prenatal care, birthing services and medical aid and delivered over 100 babies a month, without electricity or running water.

“The structure falls apart in a country after a disaster but women are still having babies and doing so while homeless, no shelter, hungry and no clean water. . . No other group of midwives are dealing with this many deliveries in a disaster zone. This is the biggest disaster in history and Philippines is unique because so many babies are born. This center is the eye of the storm” says Lim.

At Bumi Wadah they call Robin Lim “Lola” which means grandmother. Ms. Lim believes that birth keepers are the earth keepers and that by caring for the babies at birth, midwives are building peace: one mother, one child, one family at a time. She practices gentle birth, delayed cord cutting and immediate mother- baby contact. She believes babies that come into the world without trauma have the ability to fully love and trust and not do as much harm to others or the earth.

TID:

This project involves a lot of logistics/planning. Can you talk about how you researched and prepared for this journey?

DANA:

I first met Robin in person at her home in Bali while I was on my honeymoon. It was there that I learned of the storm in the Philippines and the urgency of the situation. I returned to the U.S. with a really strong urge to document the situation to help raise awareness for women’s health and to the work Robin is doing. I began doing more research on maternal health and the recent typhoon. I pitched the story to GEO magazine because I had a wonderful experience working directly with one of their writers on a prior story that I brought to them.

Once they agreed on the story I began doing the logistical research. By that point, the clinic where Robin was had some wireless and phone capabilities. I made arrangements with the women managing the clinic. I was told to bring a tent to sleep in and to pack as if I were camping. I brought a large lithium battery and solar panel kit that I could re-charge my computer and batteries from.

I arranged the travel for the writer and myself. We also put out a call for a car and driver, which was not easy. Few people had cars to begin with. I learned of a U.S. midwife that had gone over to volunteer so I spoke with her to learn as much about what I needed to bring and the current situation.

The other thing I did was collect baby goods and medical supplies to bring over. I received boxes of plastic gloves, gauze, baby swaddles, baby clothes, pre-natal vitamins, and many things that we take for granted as having access to. I brought two large, army duffle bags with me filled with supplies.

TID:

When you first got there, how did it differ from what you planned?

DANA:

I had never been in or to a natural disaster zone before. Flying over the island my mouth dropped. I could see below the amount of destruction. In some areas there was not one structure, or coconut tree, left standing.

The clinic was set up in a destroyed elementary school that had no roof. It consisted of tents– one large canvas tent was the birthing tent, and other tents were the recovery rooms. There was a generator and a solar suitcase that provided intermittent electricity. I pitched my tent with all the others. There were 5 local midwives and a few international midwives volunteering.

The hardest part for me was trying to tell the larger story outside of the clinic. There are so many layers to this story – natural disaster, climate change, over-population and lack of birth control, poverty, natural births, etc. . . . How do I weave a story out of all these elements?

Transportation was another problem. I had limited access to a car and a driver and only during daylight hours. Women were coming from hours away – often on the backs of motorcycles down almost impassable roads while in labor. I had no idea when they would arrive or return home. And of course the oppressive heat and bright sky. Basically from the hours of 6am – 6pm it was nearly impossible to make a photo outside – let alone be outside.

TID:

How did you overcome these problems?

DANA:

I loved being witness to life being born and do well in high-pressure fast-acting situations. I was there to document but I also presented myself as a human first and helped when needed: fetching items for the midwives, timing contractions, writing notes, supporting the women and holding flashlights. It was really all hands on deck. I think participating helps me not only connect with people but also to understand the story better and makes me a better storyteller.

I approach stories in an anthropological way. I make a chart of the different supporting themes and look for ways those themes intersect. I then think of visual opportunities to best show these themes and position myself to make those photographs.

I returned home with as many of the women as I could to get a sense of their living situation and try to tell a broader story. Often this meant traveling hours and arriving at a situation that I knew would not amount in a photo which is frustrating especially when you have limited time. Everyone had an intense story but not necessarily one that could be translated into pictures. I had to follow my instinct as to which women/homes had visual potential and return to those homes.

I also had to select women whose homes I could get transportation to again. I also visited hospitals and mass graveyards, walked slums flattened by the storm in order to show the different layers to what was going on.

TID:

I’m also curious how you worked logistically. Did you work with a fixer? How did you negotiate through the language barriers?

DANA:

The women managing the clinic, Tet, is extremely resourceful and she found someone that had a car. He was my driver many days and often acted as a translator. When available, a local midwife with me who spoke English came with me to translate teach me about what I was seeing.

Something tricky was how to start photographing a woman who arrives at the clinic in labor and about to give birth. Often there wasn’t time to sit down and explain why I was there. Sometimes I had to just read the situation - does the women seemed bothered by my presence? Am I in the way of the midwives? I had to go with intuition and often ask for permission after.

TID:

By in large, how did people receive your presence?

DANA:

I arrived bearing two huge army duffle bags of medical supplies and baby items. That set the stage that I wasn’t there just to “take” but that my intentions were also to help.

I also humbled myself to the midwives. I was amazed by their knowledge and skill and wanted to learn. They could sense that. I wasn’t afraid to pitch in and literally get my hands dirty. Whatever the midwives needed (including helping insert a catheter) - I was obviously there to capture the story but realize that we were dealing with potentially crisis situations and I could help if needed.

Being at the clinic gave me credibility with the women giving birth. I attended to them during their births and helped comfort them. That helped me gain their trust. I made sure when the time was right to explain in detail my intention with their photos and most all agreed that I could follow them home. I brought healthy meals and gifts for the babies to the women whose homes I returned to photograph.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Please walk us through how you photographed the moment?

DANA:

I first met Arabelle at the clinic and learned of her story.

I returned to her house a couple of times to get a sense of living her situation and in hopes of following one women through the end of pregnancy, birth and returning home. During most of my visits nothing visually really occurred. Arabelle rested on a matte for hours.

Then one evening I was invited for dinner and I got to meet the whole family – all the siblings, grandkids and her parents. It was a really joyous meal with lots of people and kids crammed around a table eating in shifts. Before, as the sun was setting and heat settling, Arabelle sat off to the side. Being that pregnant in such heat cannot be comfortable so she was adjusting her sitting positions and struck this pose. I recognized this quiet moment and how nice the light was behind her with the hint of sky and moved so that I was seated across from her.

I remained pretty quiet while photographing her here. I wanted to watch the moment unfold and not change the situation nor make her uncomfortable or feel like she had to engage me.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself while working on this project?

DANA:

Wow. A Lot. But I don’t think I realized the half of it until a few months later after I was home and learned that I was pregnant. Seeing such beautiful, natural births in the worst of conditions taught me to trust my body. Being at the clinic and learning from the midwives led me on a path towards a more natural, holistic, midwifery model of birth. I am an activist for women and mothers around the world and want to do all I can to help support healthy births.

TID:

What did you learn about others?

DANA:

I learned a lot about being a midwife and have an incredible amount of respect for them. It takes knowledge, compassion, a calm mind and skill. To then be a midwife working in a disaster zone with limited resources is even more dedication.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers wanting to do this type of work?

DANA:

It’s important to have a good idea and a good distribution model. In this economy you often have to pitch the story in many ways and piece things together to cover the costs. For example GEO magazine covered my costs and published the story first, Getty Reportage is syndicating the photos and the foundation is using the images for fundraising and awareness.

:::BIO:::

Dana Romanoff is a photographer and director whose combines her Bachelors in Cultural Studies with a Masters in Visual Communications, career as a photojournalist and passion for people to produce compelling and authentic images and films for commercial, editorial and humanitarian aid clients. Her images grace the pages of National Geographic, New York Times and publications worldwide.

She’s won multiple awards, including at Pictures of the Year International and the Anthropographia Multimedia & Human Rights Award, which brought her film “No Man’s Land” to human-rights gatherings around the globe. While working at The Charlotte Observer, Dana was among the team recognized as runner-up to the Pulitzer Prize in 2007. She is the CO-Director and Director of Photography of National Park Experience, a film series about youth and diversity in our National Parks. Dana’s work is colorful, layered and soulful and creates relationships and reveals inner lives.

You can see more of her work here: