Spotlight on Brian Cassella

May 27, 2012

Originally published 06/03/2012

TID:

Great work on getting this image, Brian. Can you tell us a little about the image to give it context?

BRIAN:

Sure, and thanks so much for inviting me to participate. I love seeing how other photographers think.

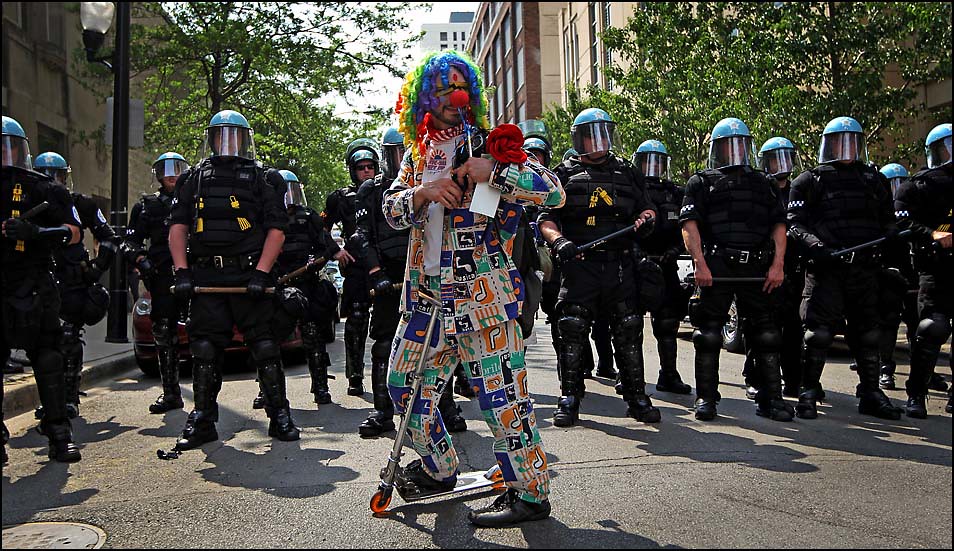

This image is from Sunday, May 20, which was the first day of the NATO summit in Chicago. Protesters had been gathering

since Friday, so this was already our third day of covering big events downtown. Throughout the week there was a tremendous

presence by Chicago police.

Sunday's march was the largest of the weekend. It started in Grant Park, wound through the Loop and ended with a rally near

the McCormick Convention Center where the summit was underway. There were thousands of marchers, most focused on

NATO's involvement in wars around the world, including veterans throwing their medals back. Afterwards a smaller group of several

hundred people remained at the corner of Michigan Avenue and Cermak Road. Chicago police would not let them move toward the

convention center, setting the stage for a confrontation.

TID:

What has the reaction been to the photograph?

BRIAN:

Very positive, even from people I wasn't expecting. From the first chance I got to see the image on the back of the camera

I knew there was some power to the punch frame. Alone, it's easy to see police brutality in it. What I’m most satisfied with

is that I had a sequence of images that told a more complete story leading up to the punch, particularly the frame with the

stick breaking over the officer's head. Our photo editors only published the images in print as a group of three, and posted it

online as an edit of nine images:

The photo has been circulated (read: stolen) all over the web, but the places where I've seen it referenced included follow-up

links back to the sequence and video. That was a pleasant surprise. Readers seem to appreciate having this deeper look at

what happened and are able to make up their own minds. It's not my role to tell them how to think, only to present the most

complete picture I can of what happened. Sometimes one photograph can't do that alone, and in this case we made sure to

only publish the images as part of this series. I've also heard from Chicago police officers who were thrilled, telling me "we did

them right." I didn't expect this, but I'm glad they can at least appreciate that we tried to present the information neutrally.

TID:

I can imagine a lot of planning went into covering this event. Can you talk about how you prepared for coverage mentally?

BRIAN:

We had several meetings and training sessions at the Tribune. There was a concern the event could bring tens of thousands of protesters,

some possibly intent on violence and property destruction. People were imagining Seattle’s 1999 WTO meetings or the police riot at

the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Fortunately, none of this came to pass.

Tribune Director of Photography Todd Panagopoulos was the field general in the newsroom and got us where we needed to be. These

rallies would meander around the city, varying in intensity until midnight. I didn't have to worry about much besides my own specific

assignments, but those evolved as situations changed. On Saturday, I started in Wrigleyville where we were expecting protesters

outside of the Cubs-Sox game. When this didn't materialize, I was rushed down to the Loop when demonstrators challenged police by

trying to cross the Chicago River bridges.

I focused on three things in preparing: First, covering both protesters and police presence fairly was critical. Second, we wanted

everything we shot to be available instantly, and I relied heavily on our WFT transmitting system with 4G cards to send as I walked. Our

editors captioned and had images online before I had a chance to sit down. And third was safety. We talked during our training session

about keeping track of escape routes and watching body language to avoid being in middle of confrontations.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while photographing the protests?

BRIAN:

Everything went surprisingly smooth. Some protesters demanded they not be photographed, but they were always on public

streets. The police presence was massive, but I didn't experience much hassling - mainly being moved out of the way as their

lines marched. (One photographer was arrested.) The most challenging time was the end of the rally on Sunday evening at

Michigan and Cermak. The crowd crush was intense, it was 90 degrees, and the police were in full riot gear wearing their

turtle suits, shields and helmets with their batons drawn.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

BRIAN:

The Tribune made sure we had the gear we needed and communication from the office throughout was critical.

I carried only what I needed. They asked us to check in with the assignment desk every hour. This seemed excessive, but

they were able to fill me in on things I couldn't see.

Our team coverage was crucial to the standoff at Michigan and Cermak. As I looked around I could see co-workers behind

police lines, overhead on a rooftop and behind me in the crowd. This made my zone near the meeting point of the police

and the protesters easier to cover. Since none of us could be everywhere, we could concentrate on what we could see.

Most assignments certainly aren't like this, but I love working in teams. I learned that at the St. Petersburg Times where the staff

is great at plotting coverage strategies.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture.

BRIAN:

After the rally most of the crowd headed west toward the El. There was a group of maybe 300 people, many young and dressed

in bandanas, who had no intention of moving. This ‘black bloc’ group was much more confrontational toward police and media.

The first thing I noticed was a line of officers in full riot gear moving into the intersection. Up until now they had lined the sidewalks.

The protesters were chanting, "NATO is east!” and pressing themselves together facing off with the police. Announcements began

blaring issuing an order to clear the area.

I squeezed forward through the protesters toward the police line. Within a few people of the front I noticed an older woman, 75 years-old

and using a walker. I tried to frame a picture of her in the crush. The officers had their batons gripped in front and were using

them shouting, "Move! Move! Move!" to shove the crowd west. Bottles and rocks flew from the crowd at the officers, bouncing off their

shields and at least one video camera.

Suddenly, maybe ten feet in front of me, I saw a white-shirted lieutenant's helmet fly off. He may have been pulling the older woman out of

the crowd and a protester knocked it loose, but I can't be certain. Immediately, I could see him and two other officers lift their batons and

begin striking the protesters directly in front. The lieutenant surged forward toward me, possibly attempting to pluck out a protester. When he

was about three feet in front of me, a protester to my left broke a stick over his head. As he fell backward, a second stick came from

my right and swung at him. In an instant, the blue-shirted officer without a helmet moved forward and took a huge swing. I was standing behind

the guy he punched and the force knocked us both back. The entire sequence from when the helmet first flew off to the punch lasted 15 seconds.

The scariest part was after this; the crush of the crowd made it hard to breathe. Everyone around me fell to the ground, and I had to get to my

feet quickly to avoid being trampled. I stopped shooting, kept a tight grip on my camera straps, and could feel hands searching my (empty)

back pockets. It took a couple minutes to pry my way a few feet and over some barricades. I stayed just out of the crush for the next two hours,

particularly when the police put gas masks on. I knew I needed to be in the middle of things to some extent to make compelling images, but

there is a line between what's productive and just dangerous. Other clashes and arrests continued, but most protesters were divided up by

police lines and eventually left.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment?

BRIAN:

Probably that I made any image at all! Luck was certainly needed. With protesters pressed against me on all sides I used

my wide-angle lens over my head, stretched between people and an army of other cameras. But that's also not to say that it's

only a matter of throwing a camera in the air and crossing my fingers. I shoot blind like this (high and low) every day, so I have a

decent feel for composition even when I can't see through the viewfinder. I'm still keeping track of my foreground, background

and focal point by aiming and moving the camera when it's not at my eye. I'm aware of how people are advancing through my frame

and adjusting constantly.

My colleague Alex Garcia was just a few feet to my right when this happened and had a GoPro video camera running. You can

get a sense of how quickly it all happened. His video is included over this interview I did for our website:

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of the making the image?

BRIAN:

I think I appreciate the adage that sports photographers make good news photographers. I haven't covered a lot of major

breaking news, but sports have been about half my job during my professional career. So while I love assignments where I can

frame a perfect composition and wait all day for the subject to walk through it, it simply isn't the reality in these situations.

You put yourself in position where you sense things are happening and know how to use your equipment on instinct. I've

learned to trust my gut on where the action is going to peak and then try to not to miss it. Some days I make all the wrong choices.

In this case, action came toward me.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

BRIAN:

First of all, be safe. Sense when you're getting yourself into trouble. I waded up to the front of the line when I thought I could

and was fortunate to make storytelling images, but I also backed up when I no longer felt comfortable. Several photographers

were clubbed and suffered injuries; being aware of everything happening around you is critical.

Always think about how viewers will perceive your images. Be sure you're transmitting and publishing images that tell the

whole story, even if it takes more than just that peak moment. Captions are critical; I saw message board postings picking apart

every word I wrote.

And don't be afraid of collaboration. Of course you're competing for the best images, but no one can be everywhere. Dividing

responsibilities fulfills the real goal of showing your viewers the most complete picture. Mine certainly wasn't the only memorable

photo from this scene. The power of this photo gallery from our entire staff on Sunday comes from the diversity of seeing by

everyone who was there:

:::BIO:::

A native of Baltimore, Maryland, Brian has been a photojournalist at

the Chicago Tribune since 2009. After graduating from the University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill he interned at The Seattle Times, the

Hartford Courant and the Cape Argus in Cape Town, South Africa. Prior

to the Tribune, Brian spent four years at the St. Petersburg Times in

Tampa, Florida.

Brian is a lucky charm for the teams he covers and has brought them

along to the World Series, Super Bowl, Stanley Cup Finals, BCS

Championship and Final Four, but then he moved to Wrigleyville. He

covers the full range of news, sports and features and loves living on

Chicago's North Side.

Blog: cassella.wordpress.com

Twitter: @briancassella