Spotlight on Bob Croslin

Aug 13, 2012

TID:

I first saw you posting these type of images on APAD and thought immediately about how difficult this must have been. Please tell us the backstory. We've also included a video that you provided to give us a little insight into your experience.

(Video provided by Bob Croslin)

BOB:

The Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary has been around for about 40 years and I’ve been dropping off injured birds to them every so often for the last 20 years. I’ve made a donation or two over the years but I wanted to find a way to help them through my photography. I approached the sanctuary’s marketing director with the idea of producing a public awareness campaign and a gallery show to benefit the sanctuary. I’m also looking for avenues to get the work published to raise awareness of the problems these birds face due to human encroachment into their environment.

TID:

How did you prepare for this shoot, or what did you to put yourself in place to make this happen?

BOB:

The marketing director was open to the idea but, as you can imagine, she is often contacted by hobbyists who want to photograph birds. It took 3 months of persistent communication as well as showing her my work to get her to open the doors. I then had to go about gaining the trust of the handlers as well as the folks who work in the sanctuary’s hospital. I had to assure them I wasn’t going to hurt or antagonize the animals. I was told by more than one person that what I was trying to do was impossible and that the birds would never cooperate. I learned from National Geographic photographer Vince Musi that if someone tells you something is impossible you should make it your goal to show them visually they’re wrong. It took four months of shooting every Wednesday to produce the Grounded project.

TID:

When you are told, "what I was trying to do was impossible and that the birds would never cooperate" what do you tell people, and what language do you use to help persuade people?

BOB:

I try to be as agreeable as possible with all of the demands but firm in my mission of making the best image possible. Everyone's first priority at the sanctuary is the welfare of the birds and I had to explain to them that I wouldn't do anything to jeopardize the health of any of the birds I was going to photograph. You have to understand that everyone at the sanctuary has an emotional investment in the health of the birds and their skepticism comes from that place. It's not that they don't like me but they have every right to question my motivation. I had to reassure them that I was a believer in their mission and that I would immediately stop photographing a bird if I sensed the bird was in distress.

I made sure to start out with birds that the sanctuary uses for educational outreach and are habitualized to human contact. These birds aren't tame by any means, but are easier to work with. After the first session, I emailed the best images to people at the sanctuary and they were blown away. After a few more sessions I made prints and handed them out to the volunteers and handlers. Everyone started to really trust me and that allowed me to work with the more difficult flighted birds.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image?

BOB:

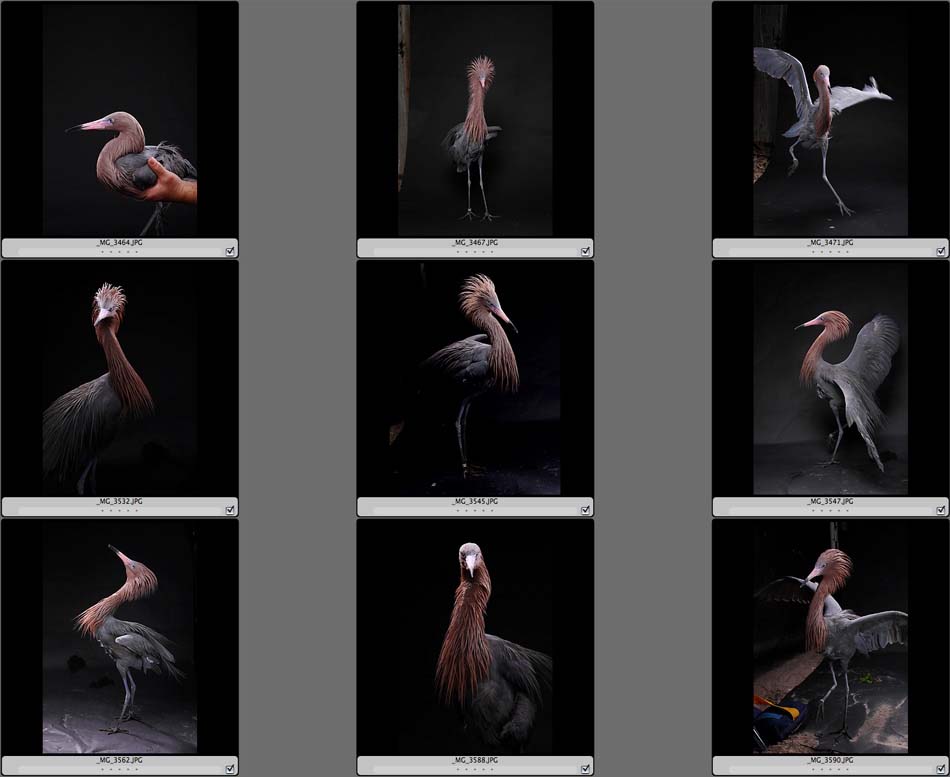

Probably the most difficult bird to photograph was the reddish heron. He’s an ornery little guy and if you get too close to him he’ll peck you hard enough to leave bloody little holes in your skin. The first thing he did when we put him on the backdrop was throw up his lunch of bait fish and then crap all over it, which meant we immediately had to flip the backdrop over. He then kept finding every hole to escape through. We had to build a huge enclosure of mesh panels, c-stands with sheets and people to keep him from escaping. He didn’t appear to be scared of any of us and it was almost like a game to him. He’d sit for a minute and then rush towards one of us and squawk. He eventually put a hole in my calf, but I made what I think is a great image of him that captures his personality. He looks like a little devil.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

BOB:

Every bird was different and the tricks varied with each bird. I shot on a black paper seamless for each bird and I must have gone through 4 rolls over the course of 4 months. We would create a pen with portable mesh panels so that the larger birds couldn’t run away but they would inevitably always find a hole to escape through. The majority of these birds are habitualized to humans so they weren’t really afraid of me but the lights and the backdrop were a little overwhelming for them. Every shoot involved a period of just letting the birds get used to the gear. Some of the birds were flighted and so we would photograph them inside a small room so we could keep them from getting away. Most of the flighted birds are so habitualized to humans and living in captivity that they don’t know how to hunt for food so we couldn’t risk one of them escaping.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

BOB:

I learned it’s important to find personal projects you feel really passionate about and pursue making images of those subjects the same way you’d go about trying to land a big client. It’s really easy as a freelance photographer to get wrapped up in the idea that every image has to lead to a paycheck but this project has been one of the most satisfying things I’ve ever done and at the end of the day, every dime I make I’d like to see go to the sanctuary.

TID:

Can you elaborate?

BOB:

It's been years since I've attempted a long-term personal project of this magnitude. I was juggling paying work with the pro bono bird work and even though I was crazy busy, I would look forward to Wednesday morning when I could photograph the birds.

It's easy to fall into the mindset that every image made needs to lead to a paycheck when you're a freelance photographer. I spend so much of my time thinking about marketing, estimates and other "business" stuff that I sometimes forget about the reason why I became a photographer in the first place: to create images that move people.

Having a project that wasn't pegged to one client freed me up to go nuts and do exactly what I wanted to do as far as conceptualizing the images. I was able to experiment with the look of the images and make mistakes without worrying about having failed. Freelance photographers don't get enough opportunities to fail. Everything is high stakes and you're under so much pressure to make publishable images that many times you play it safe. I always try and take risks on shoots, but because my jobs always involve a time crunch, I'm sometimes not able to go as far out on the limb as I'd like. With the birds I could experiment with light and how I tried to portray them. I feel like the risks I took paid off and allowed me to create a unique body of work.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture?

BOB:

Reddish kept trying to run off and one of the handlers would have to run after him, scoop him up and deposit him back on the backdrop. He would then take a moment to compose himself and then start looking for a new exit. There were 4 of us trying to make the image happen and whenever I would raise the camera and inch towards him he would puff up. Reddish is a smart bird and I could tell this was becoming a game for him. He never seemed to be afraid of me, but more like he was just annoyed. He started walking towards camera right and one of the handlers stepped towards him and as he did Reddish turned and puffed up. I made the frame and instantly knew I had made a beautiful image.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment?

BOB:

I was blown away that I was able to capture the bird’s personality. The images before and after the “frame” look like a bird trying to escape but in the 1/125th of a second I was actually able to capture what that bird is all about. I’ve been able to capture a representation of who a person wants people to think they are, and there’s always some subjectivity to it, but I look at the image I made of Reddish and I know I captured exactly who he is.

TID:

What was the breakthrough moment/time where you mentally felt you could communicate witheveryone to get the access needed?

BOB:

There wasn't really a breakthrough moment. It was a series of small steps that lead me to being trusted by the handlers - small steps like showing up every Wednesday, even when I had other things I needed to do. I created an expectation by the handlers that I was going to be there every week until I was done. I had to gain the trust of everyone I came into contact with at the shelter and that meant doing small things like giving out prints and emailing images to the handlers I worked with saying "look at the amazing image WE made." I really tried to articulate to the handlers that I was collaborating with them to make these images.

It felt great to show off the finished image and have the bird's handler tell me he'd never seen anything like it before -- even though he'd spent years working with the bird. It's an amazing feeling to show someone an image and see them become emotional.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

BOB:

Don’t take no for an answer if you believe in a project.

:::BIO:::

Bob Croslin is a Florida-based commercial and editorial photographer. After graduating with a degree in photojournalism from the University of Florida, Croslin worked on staff at The Tampa Tribune, MSNBC.com and the St. Petersburg Times, before deciding to embark on a freelance career in 2006. His work has appeared in Time, ESPN The Magazine, Men's Fitness and FastCo magazine. His Grounded project was featured at the 2012 LOOK3 festival. Croslin lives in the Tampa Bay area with his wife and daughter and cycles more than 200 miles a week when he is not shooting.

You can view his work here: