Spotlight on Allison Joyce

Sep 30, 2015

TID:

Thanks for being open to this, Allison. What a striking, and touching, image. Can you tell us the backstory?

ALLISON:

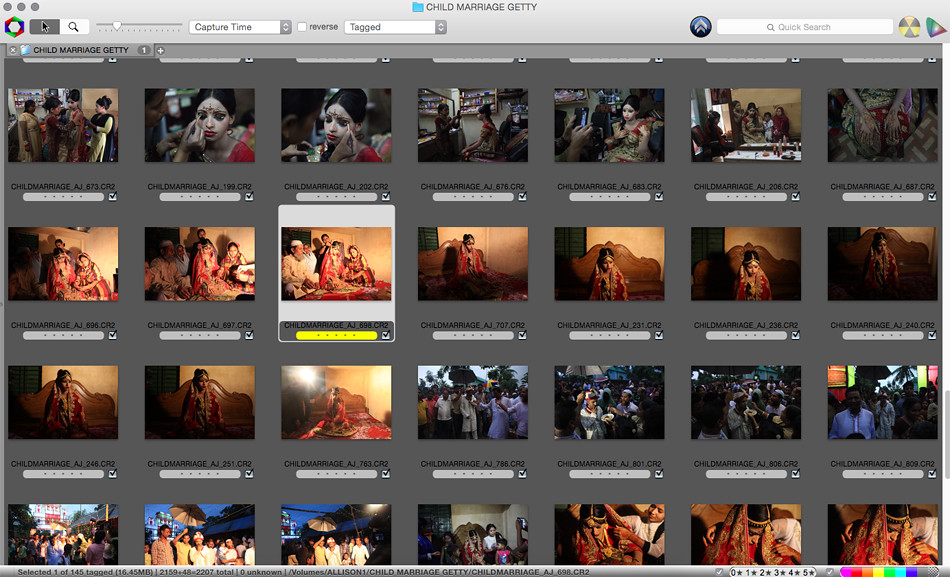

Thanks for having me on Ross, I love reading this blog. Since my first trip to Bangladesh in 2010, where I met women who were forced to marry as young as 9 years old, this has been a story I have been eager to tell. Getty accepted my pitch and assigned me two days to cover the issue of child marriage, so I made plans to photograph and interview young brides who had already been married. We just happened to pass by Nasoin's wedding tent on the way to meet another girl, and were subsequently welcomed into her wedding.

TID:

You had been living in Bangladesh and doing sone very intense work along the way. Before we examine the lead image, can you talk about your motivation to live and work in Bangladesh?

ALLISON:

In 2010 I grew restless of working for the tabloids in New York, so I saved up some money and flew to New Delhi where I then spent nearly 6 months backpacking solo and working on stories throughout India and Bangladesh. During that trip I spent a few weeks working on a story in the Sundarbans mangrove forest and it was during that time that I fell in love with Bangladesh. I returned once more in 2011 and spent the better part of 2012 saving up money in New York for my return. Finally in June 2013 I moved to Dhaka.

As far as what motivated me to live in Bangladesh, it’s a question I get asked a lot and have a hard time answering. There's something about the country that gets under my skin. The people are incredibly warm and hospitable, especially to foreigners. The countryside is the most vibrant green I have ever seen and parts of the country are seemingly untouched by modern times. It’s refreshing to work in a place so innocent and beautiful. Bangladesh is at the frontline of many of the most pressing problems facing the world, and it's full of important stories that need to be documented. I feel like I could live in Bangladesh for 100 years and not tell all the stories that need to be told.

TID:

What type of problems do you face as a journalist?

ALLISON:

In America, the media are regarded with a lot of suspicion and sometimes downright hostility. That’s not the case in South Asia, it is still a respected profession. The biggest problem I tend to have is crowds of people being over curious about me, which makes blending into the background of a story very difficult. Often times men will follow me around and mob me, so I had to stop working alone, and almost always hire a male translator/bodyguard, which provides a little bit more protection.

That said, freedom of the press isn’t really a thing. There are some sensitive stories that I need to be careful about documenting. I don’t really cover the garment industry, for example, because it's an immensely sensitive and powerful industry in the eyes of the government. Four bloggers who dared to write objectively about Islam were hacked to death by religious extremists this year alone. There have been many journalists and editors jailed for writing things that the government doesn't agree with and there are a number of them in exile overseas. A good friend of mine received death threats after publishing a documentary about rape in the country, and earlier this year I was threatened by a local Dhaka photojournalist who didn't agree with the way I speak out about women's issues, who told me that "everything I do is being recorded." Considering what happened to the bloggers earlier this year, and the sharp rise of extremism in the country, it was a threat that I took very seriously.

TID:

How did you overcome these problems?

ALLISON:

I try to protect myself by not publishing my name on sensitive stories, varying my transport and routine, and being vigilant. While Bangladesh is a far cry from a war zone, the hostile environment classes I've taken have helped prepare me for some of the unexpected things that have come my way. Other journalists try only to take private cars, vary their route to and from work, hide their identity in public. Nothing is fail safe though, recently two foreigners were executed on the streets in Bangladesh, an attack that ISIS claimed responsibility for. I feel there's a lot more the government could be doing to curb the rise of extremism and ensure safety of the press, but it's something that doesn’t seem to be a priority for them.

TID:

Regarding the lead image - how did you first develop an interest in this. How did you located a willing participant?

ALLISON:

While covering a story in the Sundarbans in 2010 I talked to many women who had lost their husbands in tiger attacks. One of the questions I asked each of them was how old they were when they were married. The youngest was 9 years old. It was shocking to me. Losing their husbands was almost a death sentence for them as they had no means to financially support themselves since they had dropped out of school after they got married and had no skills outside the home. Some of them were ostracized by their communities, who blamed them for their husband’s death, and most all of them were struggling to feed themselves . I connected a lot of their struggles to the fact that they were married so young and knew then that child marriage in Bangladesh is a story I wanted to cover.

In August when my fixer and I showed up to Nasoin's wedding and introduced ourselves, we were welcomed with open arms. Her father, a very wealthy man, had invited more than 2,000 weddings guests and was slaughtering hundreds of animals for the dinner. It surprised me because one of the biggest reasons cited for child marriage is poverty, but this clearly wasn’t the case for Nasoin. This was a happy, proud time for her family and they were happy to have me there photographing.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the minutes leading up to the main frame, and what was going on in your mind at the same time?

ALLISON:

I tried to shoot as sparingly as possible that day, because Nasoin seemed very unhappy, and a little shaken up. I didn’t want to be too intrusive . She was sitting on her bed in a small room with about 30 guests who were all vying to have a look at her while the camera man filmed her. Watching her relatives preen and prune her for the crowd and video camera felt a little bit like watching an animal at the zoo because she was so unengaged. Another thing that was so striking for me was that the entire community was complicate in the marriage of a 15 year old girl to a 32 year old man . An entire street was shut down for the wedding and 2,000 guests were invited. The legal age for girls to marry is 18, and there's no way the local officials did not know about this gigantic, loud, wedding. The energy and joy of the guests was palpable, as they danced in the street to hindi pop sounds, celebrating the marriage. This was a happy time for everyone, which was disturbing to me, but the sad reality is that child marriage is the norm for the majority of women in Bangladesh.

TID:

This body of work has tremendous importance, and has been circulated widely. What do you personally hope to achieve with it?

ALLISON:

I'm really happy that this story got so much attention, but I was surprised to learn that so many people had no idea that this is happening! According to Girls not Brides, worldwide every year 15 million girls are married before the age of 18, which is 28 girls every minute.

Bangladesh has the highest rate of child marriage in all of Asia, and the highest in the world of girls marrying off before the age of 15. 65 percent of girls will be married before age 18. Outside of the more progressive capital Dhaka, it’s the norm in Bangladesh . Whenever I go on a simple assignment I find myself asking women how old they were when they got married. Almost always they tell me they were married before the age of 16.

This speaks to culture that has not made a safe space for women and girls in public life. Women and girls in Bangladesh are dependent on men for their safety and oftentimes their livelihood. Very often parents marry their daughters off young to “protect” them from sexual harassment. Marriage is seen as a cover of respect and protection for women. By not going to school, it reduces the risk of being sexually active outside the house or being attacked or harassed while commuting.

There are NGOs who are working incredibly hard to combat this issue, but until the hearts and minds of local government officials are won, this problem will persist. For under 2 USD it’s possible to bribe an official to change a girl’s birth certificate so that she’s old enough to wed.

There are so many more women's issues to cover; women who are attacked with acid because they can’t pay their dowry or because they reject a boy’s advances, girls who commit suicide to escape sexual harassment (commonly and infuriatingly referred to as eve-teasing), the gang rape of women and girls (one in eight men in rural Bangladesh admit to having committed rape, according to a UN report). This is only the tip of the iceberg, and I hope the attention that this tiny, two day story has gotten will help me when I apply for grant funding to cover child marriage and other women's issues further.

With this story, and all of my work, I want to hold a mirror up to Bangladeshi society and say "look at this!!". It's one thing to read about the statistics. I hope that seeing the face of a frightened child on the day that her childhood ends will have impact and motivate real change.

TID:

I often ask this, but I’m curious how not only this series, but working in Bangladesh has impacted you?

ALLISON:

Living in working in Bangladesh gave me so much. I met inspiring and amazing people, and covered stories that I care very deeply about, ranging from the best to the worst of humanity. I worked for an incredibly supportive editor at Getty, Oscar Bellville, who took a chance on a lot of the off the beaten path pitches I sent to him, and provided me with not only the financial resources but the creative space to let the stories develop as they needed to. I grew immensely as a photographer and as a person.

But to be honest, living and working in Bangladesh took a huge mental toll on me. Sexual harassment and unwanted attention from men are something that women, both local and foreign, battle on a daily basis in Bangladesh. It didn't matter how much I spoke the language, covered up and dressed locally, I always attracted unwanted attention from men even when I was just walking down the street of the diplomatic neighborhood in Dhaka. Again, this speaks to women and girls not having a safe space in public life in Bangladesh. I could be surrounded by a throng of people in Dhaka and not spot a single woman. Covering some of these emotionally intense stories, working rurally in difficult conditions and then not being able to come home from them and lead a "normal" life was exhausting. It was also immensely difficult to get editors interested in stories from here unless there’s some sort of huge disaster.

On September 1st I moved to Mumbai. In a way, leaving was a huge struggle for me. It sounds silly, but it felt like giving up, like I wasn't strong enough to stay. Since most other women in Bangladesh don't have the option of leaving, I felt guilty about moving. But in the past few weeks in Mumbai I have been able to do small, normal things that I missed so much: walk the street (in a T-shirt!) without being leered at, stroll the beach without being harassed, eat at a restaurant without attracting stares from the waitstaff, and work on assignment without a hired male translator to protect me and watch my back. Dhaka will always feel like home and I will continue to work there, but being based here in Mumbai will bring me more work and will help me live a healthier, happier life.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers wanting to do this type of work?

ALLISON:

Some of the best advice I received when I was starting out was to “put in your time”. I didn’t understand what that meant then, but I do now. I was young and impatient and chomping at the bit to cover the big stories and get the big assignments, but I wasn’t ready. I skipped school and spent three years learning at local newspapers, working for editors who helped me learn from my (many) mistakes and who gave me chances and encouraged me in my career. Make your mistakes before they really count, and be patient with yourself. Success doesn’t happen without time and hard work.

Get off the beaten path, cover what you love, and what interests you. Those might be stories in your own backyard. There’s so much chatter these days about the “death of photojournalism”, rise of citizen photography, decline of the industry, blah blah blah. There will always be a place for good photojournalism. You will need to work incredibly hard and be committed 120%, you might not make much money and you will struggle, but you can make it work and the rewards will be worth it.

:::BIO:::

Allison Joyce is a Boston born photojournalist based between Mumbai, India and Dhaka, Bangladesh. At the age of 19 she left school at Pratt Institute and moved to Iowa to cover the 2008 Presidential Race where she worked as a campaign photographer for Hillary Clinton. The experience inspired her travels around the world covering social issues and news.

Her work has appeared in publications worldwide, including The New York Times, National Geographic, Bloomberg, Mother Jones, Virginia Quarterly Review, TIME, Paris Match and Newsweek. Other clients have included Microsoft, Apple, FX and Action Aid.

Her work has been honored by POYI (Pictures of the Year International) and the NYPPA (New York Press Photographers Association).

You can see more of her work here:

Currently in Mumbai

+91 989 964 6816

+91 987 396 3847