Spotlight on Zun Lee

Feb 10, 2015

EDITOR'S NOTE: This week's interview was done by Jared Soares. If you would like to be a guest interviewer, please contact Ross at: [email protected]

TID:

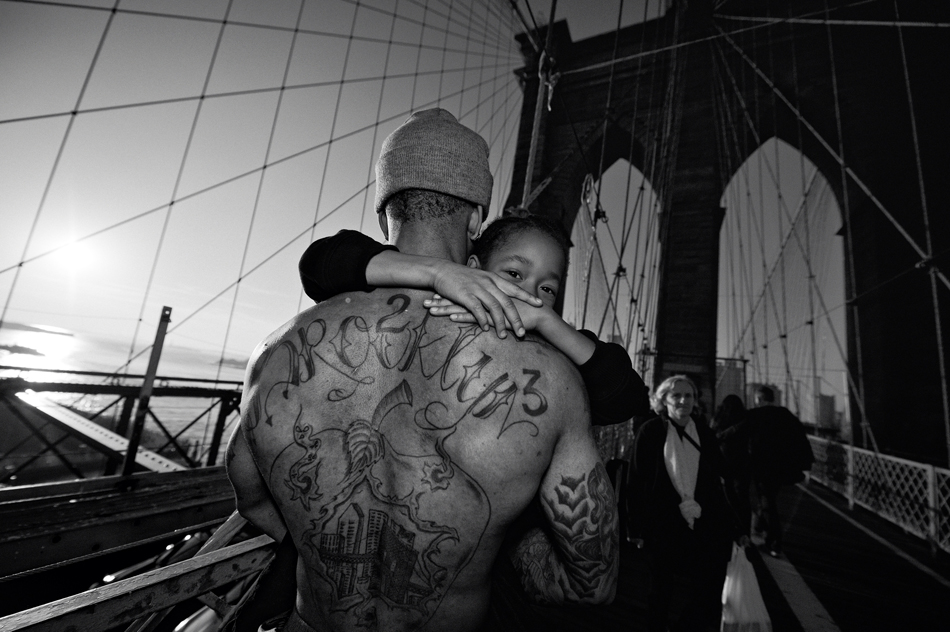

This frame suggests quite a bit of emotion between the two subjects. Could you provide some context?

ZUN:

Prior to this image, I had been working with Jerell and his son Fidel for about six months as part of my Father Figure project. Jerell is a single African-American father who lives with his son on the Lower East Side of New York. It took me a long time to initiate contact and establish rapport with this particular family. Even so, it was difficult to get to a space where we trust each other enough to share personal moments. For this series, I wanted to explore moments that don’t necessarily show families at their best or happiest, but perhaps at their most real. And a parent being overwhelmed by the day’s challenges and needing a minute to exhale and regroup – to me, that is such a moment. Showing that openness was especially important for me with respect to Jerell, whose physical appearance often intimidates people and does not readily convey emotional vulnerability. I chose this particular image because it exemplifies a key dissonance I wanted to explore through Father Figure: societal misconceptions that regard African-American men as dangerous and aggressive versus an alternate human truth we don’t often see represented.

TID:

What was the catalyst for this project?

ZUN:

Stereotypes of black fathers as absent, lazy, irresponsible deadbeats – these representations and societal perceptions have stubbornly persisted despite ample research evidence to the contrary. The flipside of this coin didn’t look particularly representative, either, with the majority of positive visuals centered on celebrity males (e.g. athletes, entertainers) or traditional patriarchs (e.g. “Dr. Huxtable”.) I became interested in showing a more differentiated notion of black fatherhood based on the workaday realities of many black families, the everyday father that gets lost in the media shuffle.

On a personal level, I embarked on this project to deal with my own narrative of father absence. In a surprise discovery, I found out that an African-American man was my biological dad, an individual who I still know next to nothing about. The fact that this subject matter hit so close to home made this project much more urgent and personal for me. Working so closely with so many families brought me face to face with an alternate side of black fatherhood that eventually helped me to get to a place of redemption.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working on the project?

ZUN:

This was my first-ever long-form project, so there was a lot of trial and error. From selecting the right families to work with, to gradually zoning in on the thematic focus, to figuring out what types of moments would narrate the story. The most difficult aspect was building the right kind of relationship with potential collaborators – many fathers and families were initially positive about working with me, but only a handful would eventually allow me to immerse myself in their lives. There were challenges regarding suitability, meaning I had to get clear about the difference between someone being a great father versus a great photographic subject: A given individual may very well be a wonderful dad but that doesn’t necessarily visually translate into something compelling.

TID:

How did you address and/or overcome said challenges?

ZUN:

In terms of finding the appropriate level of trust and intimacy, a lot of relationship building had to happen before I could begin to take any pictures. I spent a lot of time just being part of a family’s life, so the individuals would develop some assurance that I’m not there just to take pictures and walk away. Beyond that, I had assessed whether a given family would be likely to provide something energetically and visually meaningful for me to photograph. Finally, I had to open myself up in equal measure to the families I ended up working with – let them in on my story and why I’m doing this work. It was important to make myself as vulnerable as I expected my families to be with me.

TID:

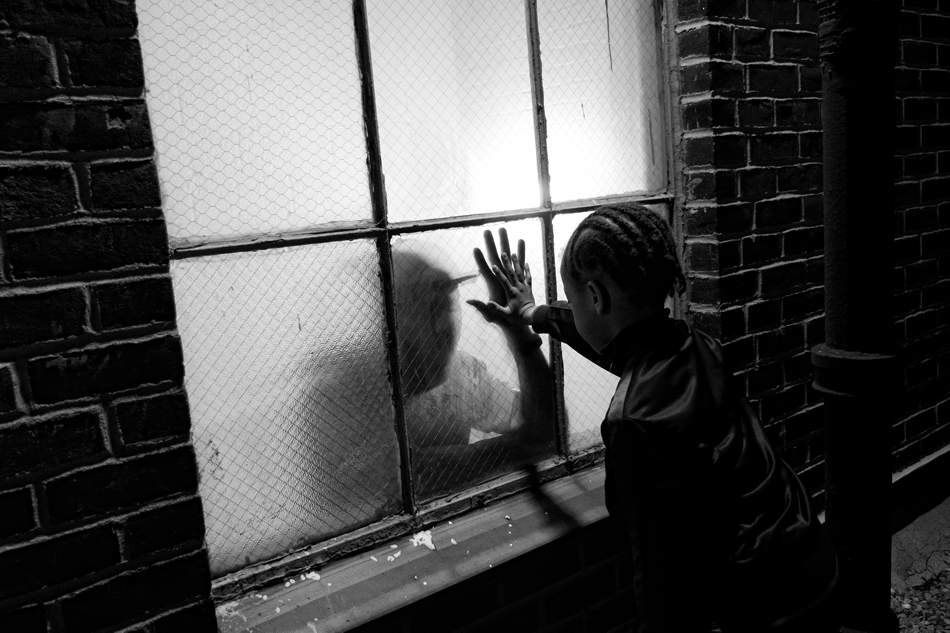

Describe the situation leading up to the photograph and also the moment in frame that you chose.

ZUN:

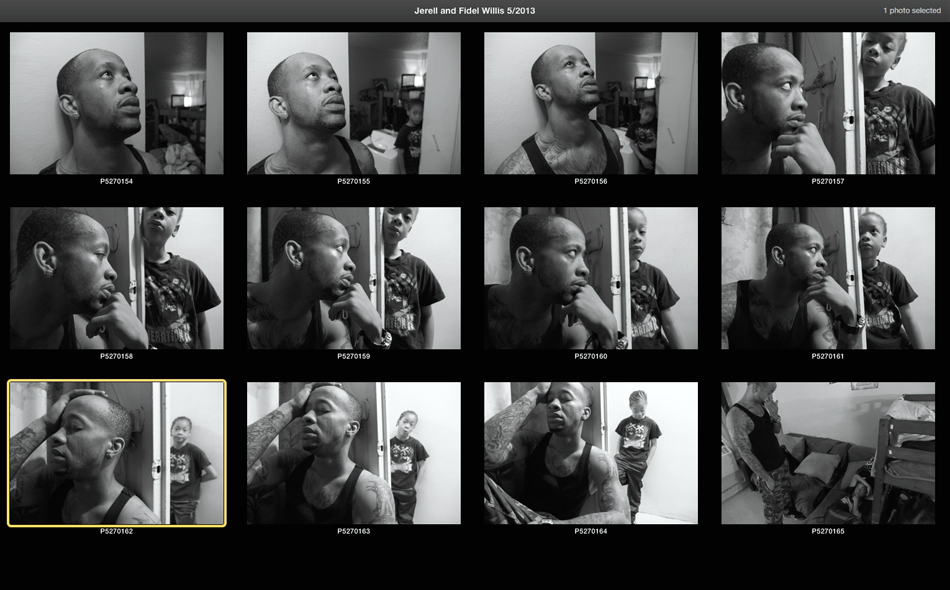

Prior to this moment, Jerell would usually not allow himself to be so open with me and the few times he did, he usually asked that I stop photographing. That day, things had been particularly challenging for Jerell, so his frustration had been building to a point where it was difficult for him to control his emotions or successfully hide them from Fidel and me. He eventually retreated into the bathroom to regroup. Too exhausted to worry about my presence, he let me follow him and stay. Interestingly, he didn’t want his son Fidel to see him in the state he was and thus he asked him to stay outside, even though Fidel was clearly concerned about his dad’s well-being. Between being allowed to witness Jerell’s vulnerability and at the same time being exposed to Fidel’s confusion and worry, I wasn’t quite sure how to negotiate my own presence, so it was an intense and awkward moment for me to say the least.

TID:

The frame you chose indicates that you were very close in terms of proximity and emotionally with the subjects. Describe how you build a rapport with your subjects.

ZUN:

As mentioned, much of the rapport-building happens outside of the realm of photography. With Jerell and Fidel, it took a particularly long time at the beginning. I had contacted Jerell on social media and it took nearly six months even just to receive a positive response. I think much of this relationship hinged on the fact that I wasn’t just demonstrating my interest in working with this family as subjects. I let them know in all my interactions that I “get” the nuances of this subject matter and that I would work with them from a place of love and integrity. Communicating my own story was also important, so empathy worked both ways. That said, building trust was never a liner process, so I had to be prepared for momentary rejection or a reset of our relationship at any time. Whenever this happened, I just had to be patient and hope that in time, some families would come around and allow me back into their lives. With many others, I simply had to accept that for whatever reason, a relationship had come to an end. After a while, you develop pretty good intuition regarding when you can push for more, and when you have to let it go.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of the making the project? How will this influence your next project?

ZUN:

There were several lessons learned; some were a natural evolution of things I had been aware of before and others were definite surprises. For me, long-form projects become more powerful and personal if you allow yourself to move out of an observer role and find a way to empathize. For that to happen, it helps if there are aspects about the people and subject matter that resonate with my own lived experience in some way. The camera no longer serves a recording tool but becomes a two-way conduit: How I worked with the families inevitably revealed as much about myself. I had to get comfortable with being so vulnerable, not only with the people that collaborated with me but with the audience that experiences the resulting images.

TID:

What advice do you have for photographers?

ZUN:

I feel I’m a relative novice in this industry, having entered it “sideways” and I anticipate I will still keep figuring things out by trial and error for quite some time. So the advice I have may be more a reflection of my own unique path but hopefully it is useful:

1. Only photograph what you love and can’t resist making pictures of. That’ll differentiate yourself consistently and will become part of what makes you stand out. It’ll also give you the compulsion and stamina to keep going when nothing and no one else will.

2. When you intend to “humanize” the people you work with, a subject matter, or a particular social issue, really think about what “humanize” means – what visual, emotional, social, and political aspects of their humanity should be narrated such that the images reflect your specific perspective versus creating a blanket statement.

3. When you work on a social issue, especially on longer-term projects, find a way to go beyond merely illuminating the issue from different angles. Look for ways you can witness an issue being addressed or overcome in some way. Don’t be afraid to show your take on potential solutions to the issue at hand (however rudimentary or “imperfect” they may be), especially if they are somewhat surprising or unexpected.

:::BIO:::

Zun is a photographer and physician from Toronto, Canada. He was born and raised in Germany, and has also lived in Atlanta, Philadelphia and Chicago.

Interpersonal trust dynamics are an important component of Zun’s work. Zun aims to re-create the essence of these dynamics to uncover everyday, untold stories of identity and connection. After his beginnings as a street photographer in 2009, Zun embarked on his first long-form project, Father Figure, in 2011. This personal documentary work examines manifestations of black fatherhood largely ignored by mainstream media. Zun used his own journey of discovery and identity formation to further this project.

Father Figure has been featured in New York Times Lens Blog, TIME Lightbox, BURN Magazine, Slate, Hyperallergic, and other publications. His trajectory as a key emerging talent has since been steep. PDN named him onto its 30 Emerging Photographers to Watch List, and he has presented at LOOKBetween and Visa pour l’Image. The Father Figure monograph was released by Ceiba in September 2014. It was shortlisted for the 2014 Aperture First Photobook Prize and landed on the best-of-year lists for Photo Eye, Vogue Italia. Zun has since completed assignments for International New York Times, MSNBC, and Open Society Foundation and is preparing for print exhibitions in the US and Canada in 2015.

Zun has a significant and growing social media presence. He can be found on twitter and Instagram as @zunleephoto and on Facebook under /zunleephoto. He is also a member of David Guttenfelder’s @EverydayUSA team.

Twitter/Instagram: @zunleephoto

Facebook: /zunleephoto