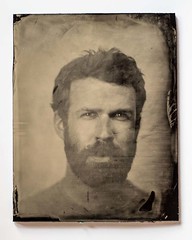

Spotlight on Ryan Dorgan

Dec 15, 2016

TID:

This is a quirky photograph, I really dig it. Can you tell us some of the backstory of the image?

RYAN:

Glad you dig it, Ross. Always enjoy the work you do and am grateful for the opportunity to chat and contribute to this archive of stories you’ve amassed here.

This picture was a little found moment away from the rowdy open jam session happening one evening at the Occidental Saloon in Buffalo, Wyoming.

The Occidental’s a historic hotel at the eastern base of the Bighorn Range that's hosted a handful of legends back in the Wild West days. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Calamity Jane, Tom Horn, Buffalo Bill Cody, Ernest Hemingway and President Theodore Roosevelt all stayed there at some point. Stepping into this place is really like stepping into the 19th century. Each Thursday night they host an open jam session at the saloon and all the old cowboys come out and take turns leading folk songs for a healthy mix of locals and Yellowstone-bound tourists.

But, it was February, and I was on my way back to Casper from an assignment up in Sheridan, so I figured it would be mostly locals that night and decided to stop in. This picture was exactly the type of scene I do my best to keep an eye out for – one that’s just a little bit off and raises more questions than it answers.

TID:

This photograph is part of a larger body of work you’ve exploring in the west. Can you talk about your journey and time in the region?

RYAN:

Yeah, it’s been a journey. I’d wanted to move west since I was a kid, and I hesitate to get into an “it was destiny” rant because that seems very cheesy and contrived, but moving out here was something I needed to do. I’ve spent the last few years here in Wyoming doing a lot of thinking and working through things that have been buried for a long time, so here’s your chance to skip ahead to the next question if you don’t like feeling like a therapist.

My dad took off a lot when I was young. It was never anything I could fault him for; he was hit head-on by a drunk driver when I was very little and as the effects from the closed head injury he suffered manifested, he plunged into a very deep, lengthy state of depression and wasn’t able to handle stress the way he could before the accident. Being a husband and a father with a high-stress job would just get to be too much for him to handle, and his way of dealing with stress was driving. He’d leave and drive down the block or around the neighborhood or around the county. The first time he didn’t come back, I didn’t know how to respond. He took a few drives where he was gone for anywhere from a couple days to six months. He always drove west.

That was a rough time for me. I was young, but old enough to realize what was going on. Old enough to see how it was affecting my mother. I found myself at maybe 10 years old feeling like I needed to be the man of the house, wondering what was so special about Nebraska or Utah or California – all these stopping points we’d get calls from once dad decided to turn around and come back to his family.

My questions were answered in the years following when he and my mom planned a couple summer road trips as dad’s health started to improve and family ties began to mend. We went west, of course. I think those trips were his apologies in a way. He wanted to show us everything he saw and share a little bit more of his curiosities with his family. Being a kid from northern Indiana, the western landscape was unlike anything I could have ever imagined. That’s when I got hooked.

So fast-forward almost 20 years. I’m 25 and am living at home in Indiana with my parents during an internship that turns into a full-time job, generally not feeling great about professional prospects in life. My college photojournalism professor Jim Kelly sends out an email that says a former student of his is looking for a photographer to fill a staff position at a newspaper in Wyoming. About a month later, my dad’s in the passenger seat of my car, helping move me west.

“You conquer loss by going to the place it happened and replaying it, saying the name of the face in the open casket right.”

Richard Hugo wrote that, and to me, it pretty well sums up what I’ve been up to out here. Yes, I’ve been working full-time as a newspaper photographer and am very dedicated to my professional work, but my personal focus has been almost a continuance of those summer road trips – seeing a new place with curious eyes and an open heart, and letting the landscape and the few people I come across while wandering around it help inform my understanding of place and answer those questions I’ve had about what makes the West so special.

TID:

How does this compare to where you grew up?

RYAN:

I always loved being outside. My parents decided to move from South Bend out to a wooded neighborhood in the county just south of the Michigan line as our family started to grow, and we had a little patch of forest in our backyard there. I’d spend dawn to dusk falling out of trees and building lean-to huts and digging holes just to dig. It’s tough going home anymore. Eventually the city crept back to us. There’s a shopping center and a hotel and apartments now where the forests and farm fields I used to run around with my friends used to be.

Over 50 percent of the state of Wyoming and 97 percent of Teton County where I live now is public land. I can roll out of bed and be in the mountains in 10 minutes. Pick the right trailhead, and you won’t see another person for as long as you want if you walk more than a mile up into the mountains. There’s a lot of room to breathe out here, and that is something that’s very important to me.

I’ve always despised development for sake of development, so I ran off to one of the few places left in this country where people had the foresight to recognize what makes this place so unique and took the difficult steps necessary to ensure that it, for the most part, stays just the way it was before people settled here permanently. Sprawl is a lasting scar on this beautiful earth and it’s made my birth home into a place I don’t feel connected to anymore, and that’s largely because there's very little natural space left to connect to.

TID:

I’m always interested in how photographers problem solve. What problems have you encountered while working in the region, and how did you overcome/work through them?

RYAN:

It’s the big empty out here. Even speaking beyond photography, everything in the rural West takes a lot more time and distance traveled to get what you’re looking for. You learn to be patient. You learn to accept that turning around and going home empty handed doesn’t mean you failed. That summit will still be there on a good weather day. The fish will be biting tomorrow. The old man with the big, white beard walking his big, white dog in a blizzard may have declined to stand for a portrait this time, but it’s a small town and you’ll see him again. I’ve found its beneficial to keep notes of the pictures I see and miss, or the pictures that almost come together while I’m out and about, because they’ll come around again.

Deer and elk and pronghorn all follow the same migratory routes they learned from their mothers. Year after year, you’ll know where and when to find them. In a place this big and empty, you run into the same people in the same places on the same days and you unintentionally get to know habits and interests and behavioral patterns just as you would by studying animals. Patience and perseverance are essential anywhere you work as a photojournalist, but out here the key is understanding that you’re playing the long game and that you might need to wait another year to see that person or that scene again. That’s okay. Write it down.

TID:

What has surprised you during your time out here?

RYAN:

I never expected such an empty place to be so complicated, and that’s mostly in regard to land and resource management. It’s easy to see the interior West as one big, empty swath of untouched land, but the reality of public resource management can be a bit of a nightmare. You have all these different interest groups lobbying for what they believe is the best use for this land that we collectively have stake in. Should mountain bikes and other mechanized travel be allowed in Wilderness areas? Should wolves and grizzly bears be hunted, and should their populations be managed by the state or by the federal government? Should oil and gas leases be allowed in sage grouse habitat?

When a private company goes bankrupt and leaves a thousand inactive natural gas wells dotting the landscape on both public and private land, are they responsible for the cleanup or is the taxpayer? If I’m buying land, shouldn’t I be entitled to the mineral rights below the surface? These questions seldom come up elsewhere in the country, but the interface between public lands and private interests is definitely something that everyone keeps an eye on out here. When Westerners say that legislators in Washington don’t understand them or their views or their needs, I think there’s some real truth to that.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself during this stage?

RYAN:

I’ve learned that I’m just like everyone else. It’s so easy to get stuck inside your own head, and that speaks so much to the importance of storytelling. We’re all figuring out our own lives and those struggles are always incredibly personal, but very rarely are they unique. That’s where the power of stories comes in – they help to bind us. I ran off to the West because my dad did, and just earlier this year he told me a story about his dad doing the same thing. Like deer following the migratory routes of their mothers...

TID:

What have you learned about others?

RYAN:

I hate to generalize, but I think there’s a much bigger emphasis on building community and keeping your neighbors close out here than there is in the more congested parts of the country. Friends and family who visit Wyoming – a place that many thought they’d never step foot – always comment on how kind and giving people are here. People are so few and far between and towns are so spread apart and small that there’s a real need to not isolate yourself and to look out for your neighbor.

TID:

Now, onto the main image. Can you walk us through the moments leading up to it, and what you were thinking while making the image?

RYAN:

I stopped dead in my tracks halfway out the bathroom door to take this picture.

There was a pretty full bar with an open jam session happening in the next room. The first thought that went through my head was, “Holy shit, this guy is so hammered he’s having a staring contest with a stuffed bear.” So I shot a quick vertical frame, then six seconds later a horizontal, then he turned and started walking toward the bathroom. Playing off the staring contest assumption, I joking asked him if he won as we were passing each other. He stopped and looked right at me, and I remember his eyes looking tired and a little teary.

“My good friend Bernie shot that bear,” he said. “He drowned in the Platte River a couple weeks ago. We look at that bear and call him Bernie now.”

The man walked into the bathroom and I just stood there for a minute or so, staring at that bear. We’d reported on Bernie’s death. He died trying to rescue his two black labs from the North Platte River just east of Casper not long before. I felt terrible. We had a weekly rotating photo column at the paper, and I followed up when my turn came around. Bernie had owned a taxidermy business in Buffalo for decades and had recently retired and moved to Casper to be closer to his family. When he sold the shop, his accountant told him he could use a tax write-off, so he decided to donate his prize Alaskan bear to the Occidental. That was about four months before he died in the river. Four months before I met that man named Andy doing all he could to connect with his old friend.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice would you have for photographers as they explore a community/region as you are?

RYAN:

First - and I think most importantly - as journalists, we have an obligation to wholly understand and truthfully tell the stories of a place or of the people who entrust us to do so. I was reminded recently that in order to do that, we first need to have the emotional maturity to wholly understand ourselves and our own stories. True empathy is not possible if you don’t know yourself and your own fragilities.

Stepping outside the realm of journalism and into personal work, another piece I took from Hugo comes from a book he wrote on poetics called “The Triggering Town.” He says that creative work best comes from a place of obsession – from assuming an emotional ownership of a word or a theme or a town – your “triggering” subject. Go to the place that calls you and own it. Dig in deep. Invest your whole self. Love and admire it and it will fulfill you.

:::BIO:::

Ryan Dorgan (b. 1987) is a photographer based in Wyoming. He has spent the last three years as a news photographer documenting the issues most important to residents of the country’s least populous state, from the effects of wolf predation on big game populations in the state’s northwest mountains to the fallout of mismanaged oil and gas leases on private ranches in the Powder River Basin. His personal work focuses on westward migration, exploring the West as a blank canvas that has been defined and redefined by the dreams and motivations of generations of Americans looking to build a new life in the nation’s vast interior.