Spotlight On Kevin German

Jul 6, 2012

TID:

This is a very powerful image, please tell us the backstory of the picture.

KEVIN:

I've been living in Vietnam for nearly 4 1/2 years now - in Saigon, or Ho Chi Minh City, to be more specific. I left the newspaper business in 2008 and moved here to begin a book-length project, however I didn't know what my subject was going to be at that time. As I began to learn more about the country, my book began to take form. I will spend the remainder of the year finishing up the book now titled, In the Footsteps of Ghosts.

The photographs of the mental health hospitals were made during my first two years in Vietnam. I was interested in the subject and I was able to gain access to the institution. I was also working on a few other small projects: one about abortion in Vietnam and another on class systems and development. In time, I realized that all the stories were connected; I was telling an overall story about the development of Vietnam and why some people benefit while others do not.

TID:

How did you gain access to this place where the image was made?

KEVIN:

It was actually kind of a fluke how this all came to be. Back in 2008, my Vietnamese was quite poor. I would surround myself with local people and take pictures of anything and everything I could while soaking up the language and culture. A friend of a friend ended up inviting me to the countryside, from what I understood, to help feed poor people. She said that they asked if I could bring 400 cookies with me. I knew there was more to that, but my understanding was limited. So I went to see what it may lead to.

After a few hours of driving we ended up at a state-run mental illness hospital. I thought for sure that I would not be able to enter, let alone take pictures. But to my surprise the doctors and patients were welcoming. We arrived around lunchtime and the patients began lining up for lunch. Almost 400 in all each received a small portion of rice, old vegetables and my cookies. What I didn't realize is that the patients were hoping that I brought more.

The doctors told me that the government pays for roughly 200 patients but the need is much higher. The occupancy is nearly twice that. When I returned home, I wrote a blog about my experience and started a week-long fundraiser via PayPal to help feed the patients for a week. Various backers donated more than $2,000 and all of it went to buy food for them.

This particular image wasn't made at that time, however. I made several trips back over the course of two years. During that time I learned more and more about the issue of mental health in Vietnam.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image?

KEVIN:

I think the biggest challenge was just understanding what I was photographing. I've seen a lot of work about mental health. It's always interesting visually. And I understand why. You get subjects coming up to and doing strange things in front of your camera. Period. But I feel it's a gross violation to just shoot without trying to understand. We have the responsibility to understand what we shoot and how we disseminate it.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

KEVIN:

I was ignorant about the issue and I didn't like that. I found education. The issues are much different from Western mentalities. Here you have to take into account the societal biases leftover from war and the Buddhist mentality of Vietnamese culture. A lot of times if someone suffers from a disability, then others think it's because that person did some thing wrong in their past life.

TID:

Now onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

KEVIN:

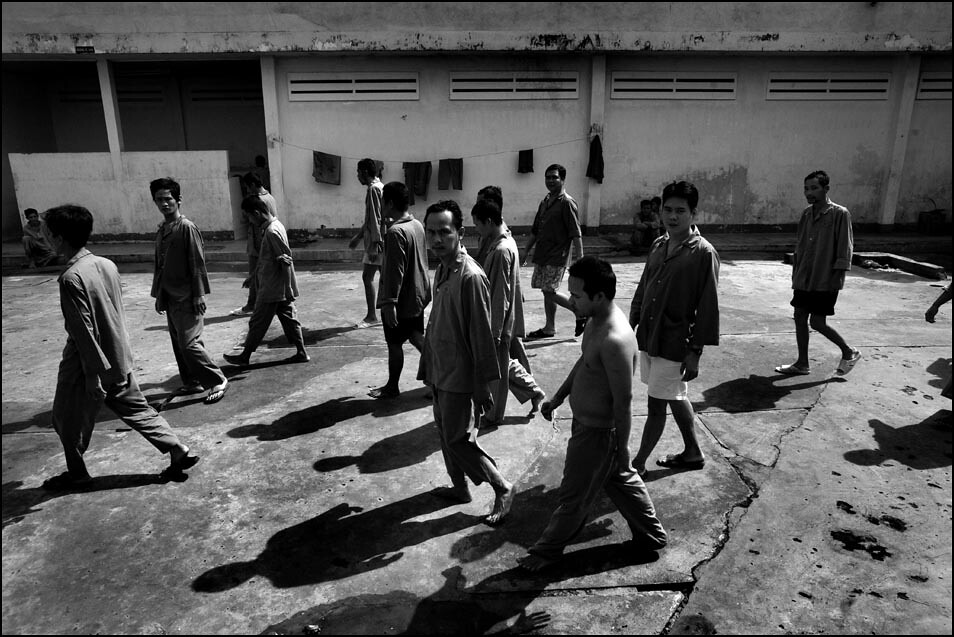

The hospital is more of a compound of sorts. There are "nicer" rooms that surround the outside of the main patient area, but the families of those patients have to pay more money for them to stay there. The majority of the people sleep on the floor on dirty mats with open doors and windows. The men and the women are separated but they can see and talk to each other through cracks in the door. I actually met two people who were "dating" each other, which consisted of having conversations through the door crack everyday.

Each male and female side has a main courtyard area that is mostly dirt. The courtyard connects to open toilets and open showers. The heat is intense and there is no privacy. It's truly more of a prison environment. When I enter the patient area, I am locked in and there are no doctors around. Just the patients and myself. Most of the time we joke and smile. But when you are around people who are unstable, any thing can happen at any time, especially if you don't fully understand what your actions may lead to.

I remember one time I had a small pack of candy with me for some reason. I pulled it out and gave some to a few patients. Before I knew it, several men were on top of me, scratching my arm fighting for the candy. I let go of it immediately and they struggled with each other over it. It was a dumb mistake on my part. After that, I thought more of my surroundings and of my actions. Ignorance is no excuse for your actions in life. This experience wasn't profound, but one among many in Vietnam that has encouraged me to become a more thoughtful photographer.

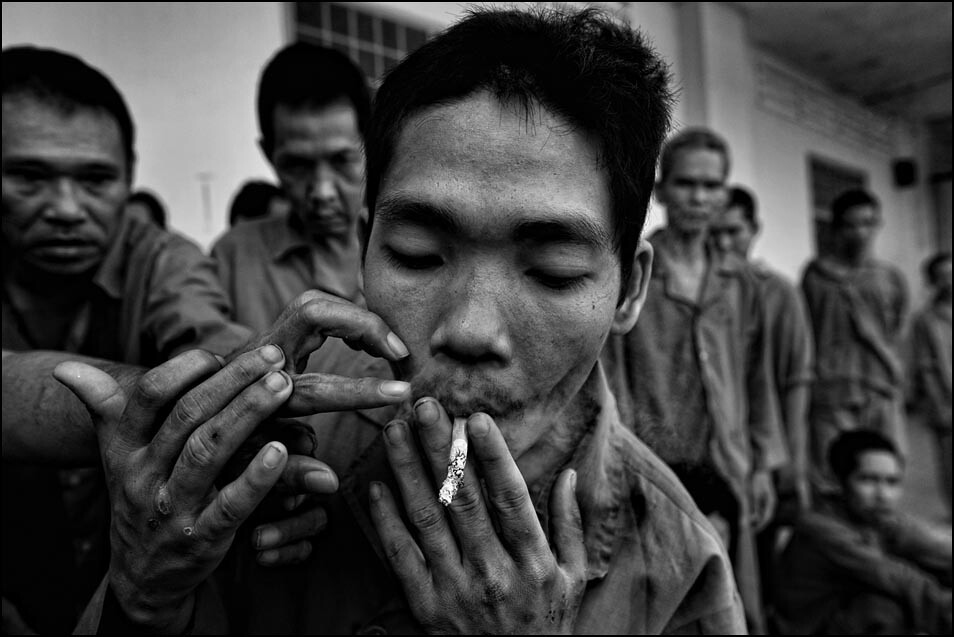

In this photograph patients are fighting over the last of a cigarette. I don't remember how they first got it but one man would snatch it from another man and so on and so on. Everyone seemed to get half of a puff. The man in the center of the frame seemed to hang onto it the longest as he pushed other people's hands away.

TID:

What was going on in your mind when you made the image?

KEVIN:

It was one of those few times where you know the situation is incredible. I've never seen multiple grown men coveting the remains of a cigarette that I see thrown on the ground or in an ash tray every day. You recognize it instantly and you only hope you are able to do it justice. I shot through the moment. I often wish I could hold off on pressing the shutter until that peak moment. But I'm not always that kind of photographer. You just try to react while being as thoughtful as possible.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment that you weren't expecting?

KEVIN:

The desperation. I was surprised over the desperation of people. When you don't have something, it becomes in demand. People will do a lot of things for a taste of luxury, especially if it's not afforded to you. Yet at the same time, I was also surprised in the kindness of others in desperate situations. I used the word "fighting," but it's not what you may think. It was more like a non-verbal disagreement. It didn't escalate. People were almost sharing reluctantly. There was one really big guy who everyone seemed to be slightly afraid of. In fact, he actually intimidated me slightly, simply because I couldn't read his face. Oh yeah, and he was big. He could have taken the cigarette right back, but someone snatched it from him and he didn't take it back.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

KEVIN:

I learned that I feel guilty making images of people where I'm only taking from them. Sure I was able to help feed them for a week by posting their photographs and other people sent money - but big deal. I still feel guilty. I shouldn't just show images of people suffering. I have a responsibility to show why people suffer, and figure out a plan to somehow help alleviate it. For me, it is to help educate the Vietnamese community about the issues of war that still affect the generation of today.

When I was younger, I always felt a pull to go to foreign lands in time of war and disaster to photograph. It was a selfish feeling, but one I couldn't shake. I chalk it up to a lack of maturity. As I've gotten older and after living in a foreign country for five years, I have come to change the way I think. I will only go some place if I am hired to do so or if I have a personal connection to what is going on. Otherwise, I simply have no business photographing in times of instability. Vietnam has taught me to become a more intelligent and compassionate photographer. And for that I am thankful.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

KEVIN:

Understand what you are photographing. It's easy to go to foreign countries and take photographs of things that are different from your own culture. But when you do that, you only contribute to the societal problems. Take responsibility for yourself and the images you make.

:::BIO::

Kevin German studied photography and journalism at Washington State University. He worked for 5 years in newspapers from California to Florida. In 2008, he left the staff of The Sacramento Bee and moved to Southeast Asia to focus on humanitarian documentaries. That same year, he co-founded the collective Luceo Images. He is based out of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. He has won numerous awards from the Pictures of the Year competition. In 2005 he was named Illinois Press Photographer of the Year. In 2009 he was named Southern Photographer of the Year. His clients include Bloomberg News, CityPass Guide, CNN Traveller, Edge Asia, Eyemazing, Forbes, International Trucking, Johnnie Walker, Monocle Magazine, National Geographic, Newsweek, The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal Asia, Time, SNOB, Vanity Fair, Windsor Plaza Hotel.

As always, if you have any suggestions or if you want to interview someone for the blog, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting.