Spotlight on David Weatherwax

Jul 5, 2012

TID:

This is a touching image. Please tell us a little of the backstory of the image.

DAVID:

First of all, thank you for asking me to be a part of this great blog. It's truly humbling to be asked to be a part of it.

This image comes from a Saturday Feature story I worked on about 65-year-old Dennis "Red" Keusch. He was a bit of a small-town legend in the area amongst the locals who remember the days of a single-class high school basketball playoff tournament. Red was part of the starting five on the 1962-63 team that had no player taller than 5-foot-10 and yet they managed to win the former Ireland High School's first and only sectional championship. One of the first things he showed me when I first visited him at his home was 8mm footage edited to local radio interviews from the year the Spuds won the title. Granted, he was a teenager in the footage, but it was such a stark contrast to see him so alive and youthful compared to 45 years later and so frail. But that was the toll that battling nearly 15 years of Parkinson's had done to his body.

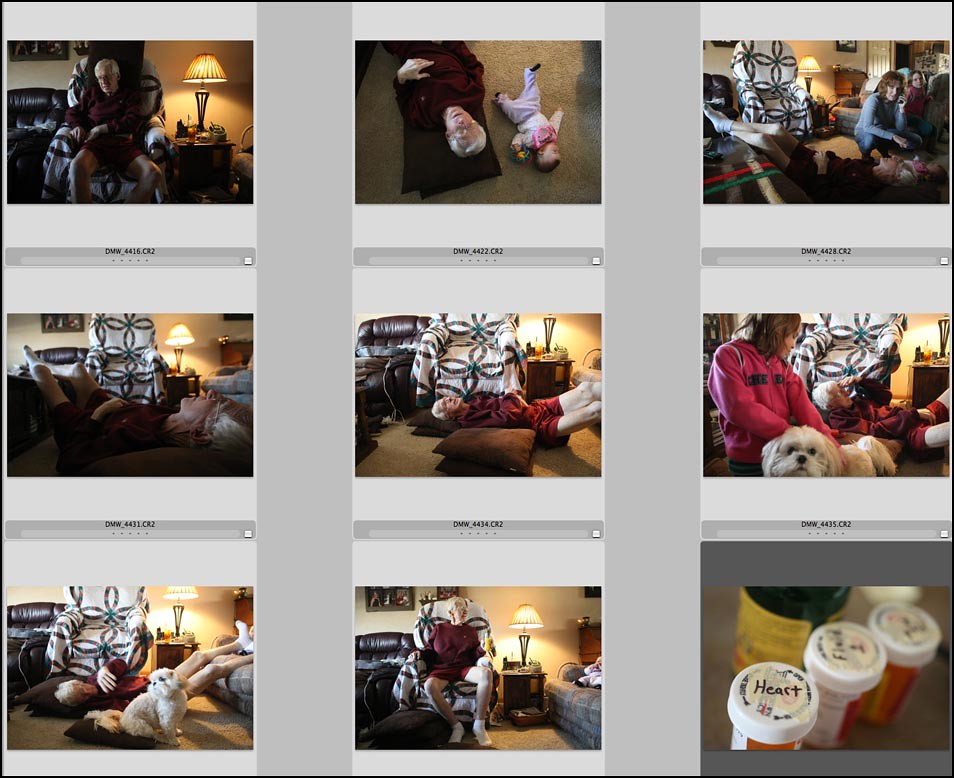

Staying as active as possible was a priority for Red, but the daily reality of Parkinson's was that his body would often shut down for varying periods of time and render him immobile. In order to combat this, Red would take up to 20 pills throughout the day to keep moving. No two days were ever the same for Red. Some days he could hardly move, and on others the medications resulted in too much movement that was debilitating. It would cause his upper body to constantly swing from side to side. Red struggled with both back and hip pain because of this excessive movement of his body. The best way he found to alleviate the pain was to lie on the floor and stretch.

TID:

This is part of a larger project. Can you tell us how you began the story and how you approached it mentally?

DAVID:

Well, to be honest, when I started this project, I certainly did not envision the story going in the direction that it ended up going. And neither did Red and his family. I first met Red when I popped in at a local bowling alley in search of a daily standalone for the next day's paper. It was a senior bowling league. Red stood out from the rest of the group. He used a walker to get around and he had this distinct side-to-side swing that never allowed him to stand still. The funny thing is, he was probably at first more curious about who I was with the cameras before I had a chance to figure out who he was. He approached me, but because of the loud commotion of the bowling alley and his soft spoken stutter, I really struggled to hear what he was trying to say to me. That certainly did not stop him from trying to carry a conversation with me. His wife, Bonnie, would later tell the reporter and me that, "He didn't know a stranger. He wasn't afraid to talk to anyone."

Just about each time he would go up to bowl, one of his fellow senior bowlers would come up to me and would tell me different tidbits of information they knew about Red and how he wasn't letting Parkinson's slow him down. As I watched him through the couple games that I stayed for, it was pretty obvious what they were telling me was true. Each throw he made progressively got slower and slower as his body became weaker. But after each throw he would promptly go back to his seat and cheer for each of the other bowlers as they had successful throws until it was his turn again when he'd then immediately pop right up from his seat and scoot his way up there to take his throw. He just would not give up even though it was visibly evident his body was telling him to.

I walked away from the bowling alley that day in awe of the individual I had met. I thought of how many other people, were they to be put in Red's shoes, would just simply roll over and let the disease just do its thing. Hell, I don't even know if I could say I'd have the strength he had. That's how I realized this was someone special, someone who could be an inspiration to others struggling through a similar situation.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working on this project?

DAVID:

One of the challenges of working at The Herald is juggling daily and sports assignments along with multiple Saturday Feature projects all at one time. I'm typically working on anywhere from 6 to 10 Saturday stories at one time. So it is very important that with each story that I'm working on that I have a clear understanding between the reporter and myself what the storyline is so I can set out to capture the moments that tell that story. It's almost unheard of that I can take a whole day to spend it with one subject from one story. The reason this was a challenge with Red's story was that some of the moments I knew I needed to capture, I couldn't quite plan for or I couldn't just ask him, "so, when can I come by to see you lying on the floor in pain," or "so, when do you think you'll have your next tumble because your coordination fails you?" There was just a lot about Red's story that I couldn't quite plan for; I just had to be there.

About five months into working on the story, there was a sudden development that came up with Red's health. What started as a routine medical procedure led to visits to the doctor and more medication which resulted in further complications that landed Red in the hospital. Sadly, he would never return to his home. Like I mentioned earlier, this was not only a surprise to me, but it was hugely unexpected by Red and his family seeing how he had been healthy and managing the Parkinson's for so long. Up until that point in the story, I had shot a good amount, but I was intentionally taking my time and really developing a relationship with Red. There was a lot I hadn't shot yet and was putting off until I really thought he was ready for me to photograph. Looking back, I think that was my own mental stumbling block more than it was really Red not being ready and open to the ideas I had. I definitely learned from that. But to complicate things further, once he ended up in the hospital, I was at the mercy of HIPPA and the local hospital. Despite having Red and his family's approval for me to visit him multiple times, I was only granted access to him one time by the hospital before he passed away. I really feel like I missed multiple moments that really could have helped advance Red's story, and it left a hole in the timeline from when he entered the hospital to when he was buried.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

DAVID:

When I start a story, I begin with an interview with the subject. It's a chance to get to know the subjects and for the subjects to get to know me before I even begin snapping frames. During these interviews, I take a lot of notes. The first chance I have to review them, I go through and I make special note of the things the subject mentioned that I think have a visual element to them and would help tell their story. The list essentially becomes a checklist that I work from to get the photos that I see are essential to the story. It's a careful balancing act of setting out to tell the story while making sure to be watchful that you are aware of how the story is unfolding and ready to adjust when needed.

With the initial interview I conducted with Red, he talked about the different challenges he faced due to the Parkinson's. For example, he talked about how he has had to learn how to fall in a way that would lessen the blow and chances of injury if he fell when struggling with his walking. He also mentioned in his initial interview how he was always proud of the Christmas decorations display he put out in front of his house every year, but how that was becoming more and more of a challenge for him. So I put myself in that situation of watching him put up the decorations by himself. I sort of gambled on the chance that he may take a fall while doing this and, sure enough, it happened. It was a challenge to anticipate it, so I would have liked to have shot it better, but the image that resulted from it worked and served its purpose in the edit.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

DAVID:

Another one of those moments that I had on my checklist to get was a photograph of him while he stretched out on the floor to help manage the back and hip pain. I had actually photographed him several weeks earlier doing this while he was alone at home. I wasn't entirely thrilled with what I shot the first time - it had happened because he had his living room curtains drawn shut and no lights on, so the exposure was really rough. I managed a few frames from it, but I knew I'd like to keep a lookout for it again down the road.

This moment presented itself a few weeks later when I stopped by his home one morning because I wanted to see his system for managing and taking his pills since he was so dependent on them. "I have to in order to exist," he said. His daughter and two granddaughters stopped by to check in on him while I was there. In the time I had spent with him, it was very obvious how much his family meant to him and how much he adored his six grandchildren. His face always lit up whenever he spoke about them.

So it was no surprise that, while battling through one of his spells where his body was both giving him fits of pain and shutting down, he placed himself flat on his living room floor and then asked to have his 10-month-old granddaughter placed down there next to him. He made every effort he could to interact with her. But it was obvious that the pain was a bit too much for him. Knowing how much he cherished her, it was so tough to watch.

I'll be honest, I didn't really shoot too many frames. I'm very cautious about that, particularly in sensitive situations. That's not necessarily a great thing because sometimes I probably shoot too little. But it's a balance of being sensitive and making sure I have it covered.

TID:

What surprised you while making images for this project?

DAVID:

It was amazing to me how willing Red was to allow me to photograph him in such vulnerable situations, especially given how so many people in the community knew Red but didn't necessarily get to see all of his daily struggles. Looking back on it now, I'm not really surprised by this. Right from the beginning he was on board. The phone call I made to him where I gave him a long, drawn-out explanation as to why I thought it was worth telling his story and how I would go about doing it with his permission was met with a simple "Yes." I was at a loss for words after his response, because I wasn't expecting it to be that easy. But I think having that transparency right at the beginning about the kind of photos I was looking to make and why they would help tell his story really helped when it actually came time to capture those moments since both he and his family knew why I was taking photos of him in those situations.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself along the way?

DAVID:

I definitely learned that I need to be more brave when capturing certain moments, and to give the subjects more credit in understanding why it is that I'm taking their photos in moments most people wouldn't think to have their photograph taken. I have to admit there's been a handful of photos in the past where I balked at taking a photograph of the subject because of their vulnerable state. A few of those I'd still argue that I didn't need the photo, because in the end I don't feel it was relevant to the story. But there are times - like with this story - where I probably should have challenged myself a bit more in those tough situations to better tell Red's story.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

DAVID:

What we do as photojournalists, it's not about us. It's all about our subjects and sharing their story with the audience. That's our main job. It's so easy to get caught up in a whole lot of different things with what we do and so easy to get frustrated when subjects don't cooperate or we can't get the access we think we should have. I became so frustrated when I was not being given access to Red in the hospital because he and his family were completely on board with me being there. I had a hard time getting past the fact that I knew I was missing moments and that's so easy to get caught up in. In the end, I think it worked for the better. It forced me to think a little less obviously about how Red's story ended. The family told me about their plan to plant the tree on the family property in his honor. We felt it was such a fitting ending to his story that we put off publication of the story for several weeks while the family waited for the ground to thaw to plant the tree. They really appreciated that.

Dave Weatherwax is the Chief Photographer in Jasper, Ind., at The Herald, a small, family-owned newspaper honored yearly for its community journalism and use of photography in covering Dubois County. Dave has thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to document the life and culture in Southern Indiana for the last few years. He greatly values the relationships he forms with the subjects he documents for the Saturday Feature.

Before coming to Jasper, he was a staff photographer and videographer for The Jackson Citizen Patriot in Jackson, Mich. Dave is a graduate of the School of Journalism at Michigan State University. He was recently awarded the 2012 NPPA Photojournalist of the Year (Smaller Markets) for his work documenting Dubois County. His story on Dennis "Red" Keusch and his battle with Parkinson's was also awarded first place in the Enterprise Picture Story (Smaller Markets).

You can view some of his winning images at: